I recently came across a game called Pony Island, and what has struck me about this game is the fact that it makes use of the idea of metanarrative in the ways it asks us to play it. And as a literary studies scholar, one whose research occasionally focuses on postmodern literature and postmodern techniques, I find myself drawn to games that make use of such techniques as well, and I find myself working to understand the points of linkage and the points of separation in the use of such methods—what is it that games do similarly to other forms when they make use of postmodern techniques like metanarrativity? What do they do differently? What is significant about such convergences and divergences?

I recently came across a game called Pony Island, and what has struck me about this game is the fact that it makes use of the idea of metanarrative in the ways it asks us to play it. And as a literary studies scholar, one whose research occasionally focuses on postmodern literature and postmodern techniques, I find myself drawn to games that make use of such techniques as well, and I find myself working to understand the points of linkage and the points of separation in the use of such methods—what is it that games do similarly to other forms when they make use of postmodern techniques like metanarrativity? What do they do differently? What is significant about such convergences and divergences?

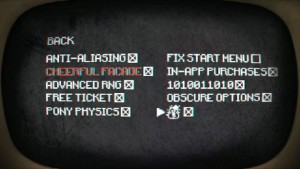

As Joel Couture at Gamasutra puts it, “Many games reward the player for using its systems properly by allowing them to progress. If you learn how to play the game well, you move on through the game’s narrative to greater challenges. Pony Island is different. It arguably rewards the player for doing something they’re not supposed to be doing: manipulating and breaking the game’s code.” And this idea of manipulation and subversion, Couture continues, is in contrast with the initial look and feel of the game: “The game looks like the sort of straightforward and kid-friendly experience you’d expect from something called Pony Island. But players soon discover that a demonic spirit hides in the guts of the game’s code, and the only way to exorcize it is to penetrate the game’s cute exterior and hack away at its properties.”

Further, Couture notes the possible challenges in establishing this narrative tone and mode of gameplay:

How do you establish a mood where the player feels that the game itself is antagonizing them? How do you instruct the player on the proper way to play the game, when playing the game properly requires you to break the game and mess around with its code? How do you make players feel like they’re doing something they’re not supposed to be doing…when it’s actually precisely what they’re supposed to be doing?

Ultimately, it seems, the game does these things through the use of metafictional elements: “Pony Island layers on levels of meta on top of the gameplay. There are faked crashes, error sounds, Steam friend messages, and other unexpected intrusions that we won’t spoil here. It seems to reach out beyond the confines of the game itself and start messing with things in your computer, or in other programs.”

Ultimately, it seems, the game does these things through the use of metafictional elements: “Pony Island layers on levels of meta on top of the gameplay. There are faked crashes, error sounds, Steam friend messages, and other unexpected intrusions that we won’t spoil here. It seems to reach out beyond the confines of the game itself and start messing with things in your computer, or in other programs.”

Indeed, Jake Muncy at Wired discusses the metafictional aspects of the game, arguing that it’s “more a game about videogames, a genre that is having something of a moment recently.” Muncy continues,

Pony Island joins other mid- to high-profile recent indie releases like The Magic Circle, The Beginner’s Guide, and Undertale that offer insight into the inner workings of games and gaming. These games use techniques and ideas literary theorists call “metafiction.” In her handy 1984 book on the subject, Metafiction: The Practice of Self-Conscious Fiction, lit professor Patricia Waugh defined metafiction as writing which draws attention to itself, to its status and existence as a created piece of art, “in order to pose questions about the relationship between fiction and reality.”

And, to be sure, the use of metafictional elements can be a tricky thing to execute, for as Muncy points out, “Metafiction, when done inelegantly, can feel self-indulgent. Hearing a game talk about itself so eagerly and obviously can prompt ridicule, even contempt, instead of introspection. Some metafictional games certainly can come off as self-important while still having a lot to offer. The best strive to expand their boundaries and give players genuinely thought-provoking questions. They are a springboard for thinking about games, and the world, in new ways. That’s the great secret with games about games. They’re not about themselves. They’re about everything else.”

And, to be sure, the use of metafictional elements can be a tricky thing to execute, for as Muncy points out, “Metafiction, when done inelegantly, can feel self-indulgent. Hearing a game talk about itself so eagerly and obviously can prompt ridicule, even contempt, instead of introspection. Some metafictional games certainly can come off as self-important while still having a lot to offer. The best strive to expand their boundaries and give players genuinely thought-provoking questions. They are a springboard for thinking about games, and the world, in new ways. That’s the great secret with games about games. They’re not about themselves. They’re about everything else.”

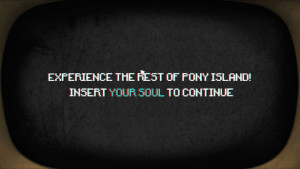

And one of the things that this metafictional “everything else” Pony Island encompasses is an exploration of who we are—especially, for example, the idea of who we are as players of the game, which is something Muncy touches on as well:

Reality here is slippery, mired in recursion: “You” are the person playing the person playing the game, a strange state that forces you to reflect on your role as both the audience for and participant in the experience. In playing this game, are you the center of this experience, or merely its facilitator? Who’s really the player—you, who guides the experience, or the fictitious player who wrestles with the devil in the machine?

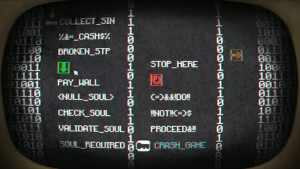

And this “devil in the machine” is both metaphorical and literal, for the game “is plagued by the developer of the in-game Pony Island, a Satanic figure who wants to steal your soul through bad design. The game uses this conceit to get at another question metanarrative fiction loves to ask: What’s the role of the creator in his own creation?”

All these questions—what is the role of the player, what is the role of the creator, how do games operate in order to allow us to ask such questions—seem significant, in part, because these are questions that not only games ask us to consider, but other media forms as well; and Muncy points this out as well: “Such questions can feel like navel-gazing, but they reverberate beyond the borders of game spaces. Systems don’t exist solely inside of games, and designers are far from the only people whose intentions and constructs we must navigate. Through parody and deconstruction, metanarrative games prod at our understanding of the systems and relationships that govern our lives.” And I think it’s this idea of systems that games seem especially able to highlight and to help us interrogate because games “ask in order to urge the player into reflection, to imbue the minutiae of mechanics and game rules with more compelling meanings. They ask in order to make themselves better. Not all of the games that try to do these things succeed, and even if they succeed, they’re not all good games, exactly. But it’s an attempt to reach beyond the box games are so often put into.” And such attempts seem worth considering.

All these questions—what is the role of the player, what is the role of the creator, how do games operate in order to allow us to ask such questions—seem significant, in part, because these are questions that not only games ask us to consider, but other media forms as well; and Muncy points this out as well: “Such questions can feel like navel-gazing, but they reverberate beyond the borders of game spaces. Systems don’t exist solely inside of games, and designers are far from the only people whose intentions and constructs we must navigate. Through parody and deconstruction, metanarrative games prod at our understanding of the systems and relationships that govern our lives.” And I think it’s this idea of systems that games seem especially able to highlight and to help us interrogate because games “ask in order to urge the player into reflection, to imbue the minutiae of mechanics and game rules with more compelling meanings. They ask in order to make themselves better. Not all of the games that try to do these things succeed, and even if they succeed, they’re not all good games, exactly. But it’s an attempt to reach beyond the box games are so often put into.” And such attempts seem worth considering.