Valve Software’s recently released documentary, Free To Play, follows the progress of three competitive gamers at “The International”, a DotA 2 (Defense of the Ancients 2) tournament*. The documentary gives us an interesting perspective on the increasing popularity of E Sports and competitive professional gaming. Indeed, several of the players, managers, and commentators featured in Free to Play make some pretty big predictions about the future of E Sports. Dendi, one of the gamers profiled, speculates “in 15 years E Sports will be bigger than football. Than basketball. Then everything.” Similarly, professional gamer Athene proclaims “A tournament of 1.6 billion dollars. That’s the future of gaming,” referring to the prize pool for the 2011 competition. These predictions lead to several questions, the most notable being: how could the increased popularity of competitive professional gaming/E Sports/Major League Gaming impact gaming culture and game design?

The comparison to sports, made by numerous people all throughout the documentary, is an interesting one. Sports are, after all, games with mechanics, rule systems, and many other design elements we like to discuss when talking about electronic games. However, it’s important to note that, while rule systems in electronic games have been rapidly evolving over the last several decades, rule systems in sports are generally more rigid and require substantial consensus and compelling reason to make any major game play changes. For instance, many of the rule changes passed by the NFL owners this year refer to clarifying precisely what constitutes a particular foul or clarifying how play review happens—these rule changes don’t so much change the game play as they do attempt to account for human error in interpreting and executing various rules systems.

In contrast, electronic games release patches and updates all the time that have major impacts on how the game is played. League of Legends, a popular MOBA game in E Sports, released a patch in November (patch 3.14) that brought substantial changes to a number of characters and altered the balance for the entire game. By buffing the various abilities of “support” champions, the way players were able to build and play these characters changed from being a very item-dependent style of play to introducing a buffing-based play-style and opening up the possibility to use “support” champions in the caster role. Of course, this isn’t the only example of this phenomenon; anyone that’s played an MMO for any amount of time (World of Warcraft, I’m looking at you…) is familiar with the crushing despair or soaring hope that comes with reading about class changes in patch notes. And here, a brief moment of silence for late WOTLK-era ret pallies. May you rest in peace, sweet DPS.

Would increased recognition of E Sports lead to more rule standardization? It’s hard to say precisely, but if we look at other competitive games as models (chess, football, etc.), the answer seems to be yes. But there’s a further design question to think about: what would it mean to design a game to be watched, rather than to be played? Interestingly, Valve’s documentary offers some hints. At several key moments in the tournament, the film switches from using actual in-game footage of the matches being shown to displaying cinematic animations created after the game (56:45-56:51 is one example). The suggestion, given the timing of these particular extra-game “cut-scenes,” seems to be that the raw game footage is, in and of itself, not dramatic enough for a large audience. Certainly these cosmetic enhancements don’t appear in current tournaments, but they do suggest an increased attention not only on the player, but also on any passive watchers that might be present. While game design has traditionally been about the play experience, both E Sports and the larger community of streamers are creating a market of players who watch as much (or possibly more) than they play.

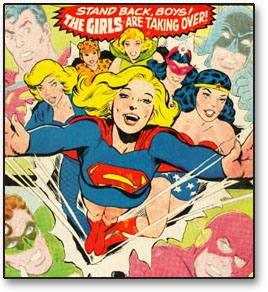

The above issues refer more to game design and production than they do to contemporary gamers. However, there’s another looming issue here that requires us to ask some hard questions about the gaming community: what role will gender play in the future of competitive professional gaming? It’s notable that the only two female gamers given any real amount of screen time in the documentary are Tammy Tang, member of the competition team PMS Asterisk and participating here only as a commentator, and the anonymous girlfriend of one of the main players in the film, mentioned as a gamer without any other background information. Indeed, Tang refers to the popularity of E Sports in China by saying “in China.. the girls like their boyfriends to be DotA players.”

As Charlotte explored in this post, online games aren’t exactly a welcoming place for female gamers. Having spent my fair amount of time in WoW RBGs, I can certainly understand why women aren’t pursing competitive gaming in large numbers. Thus, general lack of visibility in online and competitive games is mirrored in a general lack of women on competitive professional teams. Further, there is a great debate in many gaming communities about whether women should play in separate, female-only tournaments or not. While some players argue that these “ladies-only” tournaments give female players a chance to develop the types of networks and support that is harder for them to find in general tournaments, a number of others point out that this nonetheless continues the problematic perception that female gamers just aren’t as good.

So what do you think? Is competitive professional gaming the wave of the future? What changes could a codified system of E Sports bring to the average gamer?

*It should be noted that Valve owns the intellectual property rights for DotA, created DotA 2, and runs/funds “The International”.