Recently, I played through Kiva Bay’s game 12hrs, a game in which players are thrust into the role of a homeless woman trying to survive the night. Suffice to say, 12hrs is a harrowing experience in general, but unusually so here because I initially played as part of a group. As part of a class engaging with Johan Huizinga’s Homo Ludens and its definitions of play as fun and also separate from “real” life. In small groups, we were all playing games that challenge both looks at play, games that aren’t particularly “fun,” and games that certain challenge how we think about life, even if they aren’t necessarily 1:1 reflections of life.

Our group was thrown a very early curveball when we were asked, before getting into the game, to name our character. We looked at each other for a long moment before anyone spoke up. I don’t even remember who asked it — maybe it was me, maybe one of the men I was playing with, but we started with a difficult question that both was and wasn’t directly related to the task of naming: “How seriously are we going to take this?”

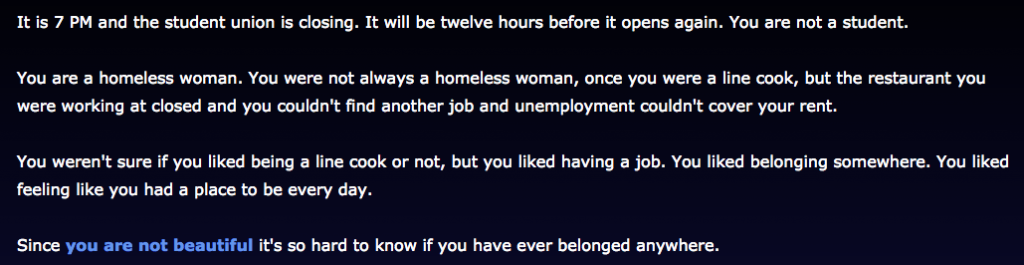

At the moment in 12hrs we were asked to name our character, we had little information about the central female character — really just what you see above (there is an additional description that we had not yet clicked, and which I won’t reveal here; it’s there, in the linked text in that screen). Should we give her a traditional “beautiful” name for a “beautiful” girl, just to buck the system? Would that be a more terrible burden, to bear a name often associated with a pretty-girl name in pop culture, if you struggle with your own sense of beauty? Would a harsher name, a more stark name, be easier? And should we be silly, and offer up something more light-hearted, not a “real” name but just a joke, since we were playing together, in class, and had no idea what was in store for us? Someone suggested Ursula and we debated it, because maybe that was a villain name, but we had nothing else. For us, the woman became Ursula, and we went on. But I thought about that act of naming all day long, and into the next, when I played through 12hrs alone (with a character named Sasha). How had the act of naming Ursula guided our play?

My partner and I sometimes play in very similar ways, which has allowed us to turn single-player games into multiplayer experiences, as with our team efforts in State of Decay: Breakdown. But in RPGs, we are very different; his characters, when he is allowed to design avatars, are ridiculous, with bright hair and warped features (if he doesn’t just go with the default), and sport names like Potato Jones. I, on the other hand, always create for myself a persona and at least an attitude. The name I choose, as much as anything else, determines how I will approach the game. Will I be selfish, a “bad” character? Will I be a white hat? How will I operate in this world I am entering? My name is part of that process, and when I name a character, I am bringing them into a state of being. Creating them, and the story I will shape around them.

This idea of creating and shaping game experiences is something that has been much on my mind lately. What if I’d taken a cue from my partner and named my character in 12hrs Fiddlesticks McGhee? That disconnect allows him to play without much thought, to “game” the game and do whatever he wishes in any particular scenario or whatever might get him the best outcome (the best rewards, etc.) with no fear of death, but it also allows for a carefree exploration, the freedom to try things just to see what might happen. With a throwaway name, I might have been able to approach 12hrs’s experience without care for my heroine’s fate; I could have experimented just to see what might happen if I chose risky options. Instead, I undertook decisions with care, considering consequences, worrying over losing — not least because we had lost in our in-class playthrough and I knew at least two of the possible fates lurking for Sasha if I made the wrong choices, and they were terrifying.

But were they only terrifying because I had humanized Sasha by naming her, by creating an identity that felt like a person? The character in 12hrs isn’t real, any more than any game character is; the game was built in Twine and is a series of rules and procedures and nothing more. The only humanity Sasha possessed was what I assigned her; even the pictures are only pictures, drawings produced by the creator. There is nothing inherent.

I don’t always need a connection to play games; I can’t even begin to count the hours I’ve put into games like those in the Civilization series, without any thought to crafting narrative as I go, and when I play something like The Sims, I’m never interested in the game, only in building elaborate or interesting houses. I don’t care who lives in them beyond the fun of downloading player-created outfits. I’ve never tried to attach a narrative to a game like Tetris, or Two Dots. But when I’m handed a narrative, or am asked to enter into a world, I enter into it with a certain base level of empathy for its inhabitants. If I can’t maintain that, I quit playing the game and move on to the next story, the next experience. That is the great mystery for me: where does that come from? What drives it? Game length seems to have little to do with it; I can be just as invested in a game like 12hrs, which can reach a win state in some 25 moves, as I can in a game like Mass Effect. But I’ve never finished the main quest line in any Elder Scrolls game; after a hundred hours of side quests and mucking about, I tend to lose interest. I grow weary. My empathy and connection is not endless, but has limits. How are those drawn? I’m not sure. All I know is that I sweated over keeping Sasha alive, just as I agonized over Shepard’s choices in Mass Effect, just as I bit my lip all through both seasons of The Walking Dead.

I don’t always need a connection to play games; I can’t even begin to count the hours I’ve put into games like those in the Civilization series, without any thought to crafting narrative as I go, and when I play something like The Sims, I’m never interested in the game, only in building elaborate or interesting houses. I don’t care who lives in them beyond the fun of downloading player-created outfits. I’ve never tried to attach a narrative to a game like Tetris, or Two Dots. But when I’m handed a narrative, or am asked to enter into a world, I enter into it with a certain base level of empathy for its inhabitants. If I can’t maintain that, I quit playing the game and move on to the next story, the next experience. That is the great mystery for me: where does that come from? What drives it? Game length seems to have little to do with it; I can be just as invested in a game like 12hrs, which can reach a win state in some 25 moves, as I can in a game like Mass Effect. But I’ve never finished the main quest line in any Elder Scrolls game; after a hundred hours of side quests and mucking about, I tend to lose interest. I grow weary. My empathy and connection is not endless, but has limits. How are those drawn? I’m not sure. All I know is that I sweated over keeping Sasha alive, just as I agonized over Shepard’s choices in Mass Effect, just as I bit my lip all through both seasons of The Walking Dead.

Perhaps, after all those side quests, when my Elder Scrolls characters were able to tie dragons in knots and knock down barbarian hordes with a single blow, I felt confident enough that the world could go on without my active involvement. Surely my warriors could handle anything, even if I wasn’t there to pull the strings. But in a game like 12hrs, there’s no leveling. There’s only a struggle, and there’s no looking away once you’ve entered that world, once you’ve given that character a name. Perhaps that’s part of what defines the difference.