(No direct spoilers here for episode five, but instead just general discussion of narrative structure and larger considerations of the game as a whole.)

Since the release of the first episode, my experience with Life Is Strange has been a series of ups and downs, but as the story has come together, episode by episode, I’ve leaned more toward the positive. These five episodes have been intense, wild at times, full of emotions (sometimes frustrations), but as I finished “Polarized,” the final chapter, I discovered much that overturned opinions I’ve built over all the aspects that came before. Moments I’d disliked were brought back and shifted, sometimes in hilarious (and unnecessary, but sharply aware) ways, and sometimes in ways that required a complete reconsideration of my feelings on characters and on the game itself. The game I thought I was playing all this time was not quite the game I finished. Since the second episode, I’ve been kicking myself over certain decisions that seemed right, in the sense of trying to do good and help others, and in episode five, at last, that felt confirmed: the right decisions here can often be terribly wrong.

Since the release of the first episode, my experience with Life Is Strange has been a series of ups and downs, but as the story has come together, episode by episode, I’ve leaned more toward the positive. These five episodes have been intense, wild at times, full of emotions (sometimes frustrations), but as I finished “Polarized,” the final chapter, I discovered much that overturned opinions I’ve built over all the aspects that came before. Moments I’d disliked were brought back and shifted, sometimes in hilarious (and unnecessary, but sharply aware) ways, and sometimes in ways that required a complete reconsideration of my feelings on characters and on the game itself. The game I thought I was playing all this time was not quite the game I finished. Since the second episode, I’ve been kicking myself over certain decisions that seemed right, in the sense of trying to do good and help others, and in episode five, at last, that felt confirmed: the right decisions here can often be terribly wrong.

Since episode two, when we discovered the vastly different Kate stories, we’ve known that choice matters in Life Is Strange, but as part of that storyline, I discovered that some of my decisions around Kate, such as telling her not to go to the authorities, such as trying to gather evidence — choices I would stand by as the safest, most “correct” ways to proceed — had consequences of their own and impacts on Max and Kate’s friendship in my game. In “Polarized,” a decision I made in “Dark Room,” which saw me rewinding multiple times just to make sure I managed it, had the potential to cause a character’s death. I stopped the game for a bit then to consider the implications. All along, I’d constructed my Max as a little uncertain, maybe a little too earnest, but as someone trying to do good. I wanted to save people. I comforted those who’d been hurt. I tried to stop people from being hit with footballs and cars and all manner of things. I always helped poor, unlucky Alyssa. And doing the right thing, the only thing, had led to something horrible.

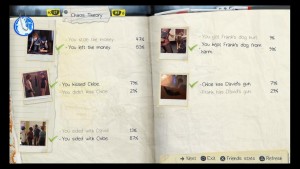

The game didn’t make a big deal about it; there was no text overlay to let me know I’d caused it. But dialogue and events connected everything for me, and I went back then, studying the decisions the game had tracked. So many focused on moments that defined Max’s sense of right and wrong, and the way she conducted interpersonal relations, even if those implications weren’t obvious at the time players are faced with the choices. Some seem so small, and yet they close off entire sections of plot while opening others.

The game didn’t make a big deal about it; there was no text overlay to let me know I’d caused it. But dialogue and events connected everything for me, and I went back then, studying the decisions the game had tracked. So many focused on moments that defined Max’s sense of right and wrong, and the way she conducted interpersonal relations, even if those implications weren’t obvious at the time players are faced with the choices. Some seem so small, and yet they close off entire sections of plot while opening others.

Late in “Polarized,” this is brought to the forefront. There are moments throughout the final episode that speak to player reaction to certain elements (those damned bottles from the junkyard make another appearance, for instance, and despite the tension of the moment, I laughed aloud in admiration), but there is a particular scene near the end that forces the player to confront Max herself, and the player’s construction of her. Who have you been all this time, and what were your motives? Have you, the player, been experiencing a story or have you been trying to game the system? What did you hope to achieve? While again, this isn’t what the game asks directly in that moment, the subtext felt very clear to me: there’s no winning. There’s no losing. Everything simply is, based on the stories we’ve each built. And there’s something breathtaking about that direct confrontation, that challenge to players, that engagement with narrative within the story that also bleeds out to address not just what we’ve played, but how.

Life Is Strange is still a game, and with that there are limitations; we are limited to this choice or that in many cases. The paths we can take are not infinite. But in this episode, the player’s experience in following along, in making those choices, is questioned. There’s thoughtful pushback here, but not just for the sake of discussion; everything here builds to the final arc, and serves to challenge the player in considering just what, at last, they will do.

It’s not all perfect — there are some issues here worth exploring, things that happen as time twists further than ever before, and we see some different depictions of certain characters, along with continued use of Native American artifacts and culture, the fact that the core cast is thin, white, and attractive, the way certain horrifying themes are treated with care while others get shunted aside for narrative convenience. Just gaming industry things. We all know how it is with these things that should be rightfully critiqued, and will be, along with others, but there’s so much here that is revolutionary that it’s difficult to overlook all that Life Is Strange brings to the table.

Whatever else can be said about Life Is Strange — and I’ll say a lot in the coming weeks, I think; we all will — I must start with this: I’ve never worried so much, hesitated so many times, paused to think, or take breaks so often. I’ve never sweated choices like this. I’ve never pulled my hair or stopped to talk through an in-game decision with a friend like this. There’s never been, for me, a game like Life Is Strange, no narrative experience that has quite matched it. I’ve railed at moments that only made sense an episode or three later; I’ve changed my mind to this and that and back again, and now, at the end, I’m still not sure about my decisions, or my feelings, or really anything at all. In that sense, Max’s journey has been like my own, like anyone’s; we look back, wondering if we chose correctly, and we struggle with the unfair outcomes of decisions we undertook with great faith and better intentions. Life isn’t just strange, but terrible, and hard, and sometimes the worst decisions are the ones that make us happy, and the “right” decisions are the ones that can ruin everything. Maybe that’s a purposeful move here, to make us think back about trying to metagame and choose “correctly,” or maybe it’s just a reflection of life. Maybe it’s both. Regardless, this is the kind of game we need, a game that challenges our boundaries and perceptions, and the things we take for granted, a game that troubles our notions of ethics, character, and narrative and that drags us beyond our expectations of games and into new, unexplored territory.