When I was kid, my rubric for normalcy was grounded in the appearance and texture of hair. As a biracial child with an ever present African American mother and absent father and a sea of white peers, I found myself stuck in a conundrum: What am I? Searching for a way to make sense of my non-binary appearance, I managed to construct a way to represent my racial identity: If my hair was up, I was Black. If my hair was down, I was White. It should be noted, though, that my dark brown, red-imbued curls were rarely ever down. As an adult, I find myself in the same shaken box of l imitations when it comes to racial representation – what does my hair say about my identity? How will onlookers construct their expectations of me if my hair is down, up, curly, or straight? Will someone attempt to put their hands in my glorious mop because they’ve never seen such curls up close? Will someone ask the dreaded question: So where are you from? My mother’s womb. You? As I’ve continued to be cornered into saying what I am rather than being because of my racial ambiguity, I’ve searched for new ways to construct my identity. As a gamer who hasn’t often experienced seeing myself onscreen, I keep picking up my console controller, or opening up Steam for a new a game, looking for me – unruly curls and all.

imitations when it comes to racial representation – what does my hair say about my identity? How will onlookers construct their expectations of me if my hair is down, up, curly, or straight? Will someone attempt to put their hands in my glorious mop because they’ve never seen such curls up close? Will someone ask the dreaded question: So where are you from? My mother’s womb. You? As I’ve continued to be cornered into saying what I am rather than being because of my racial ambiguity, I’ve searched for new ways to construct my identity. As a gamer who hasn’t often experienced seeing myself onscreen, I keep picking up my console controller, or opening up Steam for a new a game, looking for me – unruly curls and all.

Let’s face it – the gaming industry lacks representation of people of color, particularly African Americans, as designers, but also onscreen. This lack of representation at all levels has led to a deficient understanding of the diversity of black woman-hood. What I’ve found in my parsing of games criticism is mostly discussion and acknowledgement of how African American males are portrayed, or are not, in video games – as usual, African American women remain neglected, secondary, unimportant tropes of hyper-sexual sass. That’s problematic. While there are games with racial diversity, State of Decay, Destiny, Uncharted, GTA, Saints Row 3, these games and others continuously perpetuate stereotypes about Black women in the restricting ways we’re allowed to emerge. Sidney Fussel explains that

“while all women in games are subject to staid metrics of desirability, black women have their blackness negotiated in a way that assumes blackness itself is undesirable.”

Not desirable. From the time we’re little and playing on the swing-set, we’re conditioned to believe that Others are undesirable. My little White friends didn’t find my brown ambiguity attractive or my curls likable – it was quite the opposite. Though the playgrounds are now classrooms, offices, higher ed campuses, the need to for my peers to know what my Otherness is remains. Their efforts to remind me of my deficiencies in meeting their standards for physical beauty and racial inclusion have only strengthened over the last 25 years. And so while 25 years have passed, this notion of African American women being undesirable continues to infiltrate game designer’s decisions to routinely whiten our features or even make certain hair-types impossible to achieve. But who am I to complain about the design of Black or African American women? I speak up and maybe I get the Whoa, hey, you’re biracial – you’ve already been whitened; you should be able to find someone you identify with in one of these games. Eh. You’ve missed the point – diversity among Black women. There are multiple skin tones, multiple levels of emotional strength and empathy, multiple hair textures, multiple moral associations, multiple types of women. You can’t create one type of Black woman, adapt her from game to game and not expect us to notice.

Classic Example

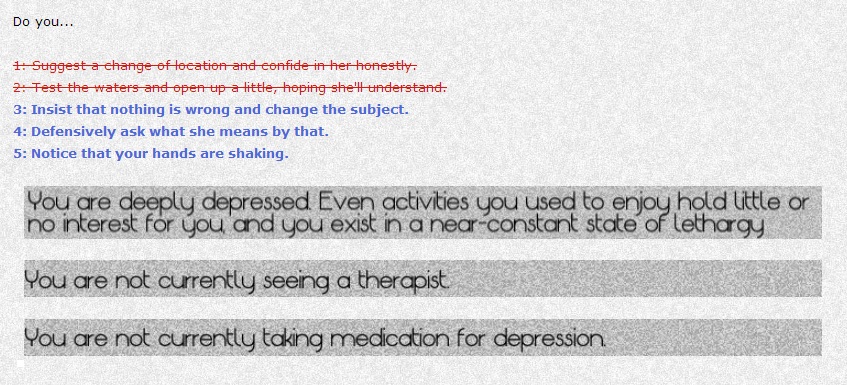

Prior to the this last year, I’ve not had a lot of experience with playing games that have a character design component. My journey with Destiny: The Taken King, radically shifted that for me when I realized, in my first interactions  with the customization features, that I might be able to create an avatar with my complexion AND my hair. I may have peed my pants a little with excitement. (I didn’t.) Inevitably, the color pallet skips that tone between honey and toasted caramel. So be it. But hair. Oh my goodness. Hair. Scrolling through the hair options, I just knew that these curls of mine were going to pop up one ringlet at a time. I scrolled. Scrolled some more. Kept scrolling. Dismayed, I eventually settled on dreadlocks. I’ve secretly always wanted them, so I might as well go for something I want rather than something I am or have… right? Interestingly, Evan Narcisse talks about this in his take on natural hair but from the male perspective:

with the customization features, that I might be able to create an avatar with my complexion AND my hair. I may have peed my pants a little with excitement. (I didn’t.) Inevitably, the color pallet skips that tone between honey and toasted caramel. So be it. But hair. Oh my goodness. Hair. Scrolling through the hair options, I just knew that these curls of mine were going to pop up one ringlet at a time. I scrolled. Scrolled some more. Kept scrolling. Dismayed, I eventually settled on dreadlocks. I’ve secretly always wanted them, so I might as well go for something I want rather than something I am or have… right? Interestingly, Evan Narcisse talks about this in his take on natural hair but from the male perspective:

Any conversation about black hair is, at its root, about more than the follicles growing on a given body. These talks are really about the intersection of personal choice and inherited standards, the crossroads where a body decides what products and treatments they’re going to use to give their hair a certain look. Video games also get their steam from the friction generated at that crossroads. People who choose to make games or identify as gamers have historically rubbed up against cultural snobbery and moral panics, the result of standards that dismiss games as mere commerce…But bring up the medium’s shortcomings and you often get flustered defensiveness in response. One of those shortcomings is in the lack of diversity of the people making and portrayed in video games.

In this discussion of natural hair and the portrayal of Black [male] characters in video games, Narcisse uses his own experiences as a stepping-stool, echoing the same question I am asking: Where am I? The ideas that Black hair is, at its root, about…the intersection of personal choice and inherited standards are warranted discussion points – but let’s branch this out to include women, a diverse representation of Black women that is. If video games get their steam from said cultural friction, what they’re creating is not choice for women of color to play with, but a societal expectation, a standard if you will, of what we’re supposed to be. I don’t have an afro. I certainly don’t have dreadlocks, but I also don’t have fine, oily blonde hair. I’ve got curls. I’ve an amalgamation of identities ringletting around my face. While my hair routine is as unique as Narcisse mentions his to be, albeit a bit longer and likely more expensive, the problem, for me, isn’t what my routine is, it lies in understanding where my agency is in choosing my racial identity when society attempts to say (by not representing me onscreen) that I don’t exist as I am; I exist as they expect me to, as they wish me to.

Earlier this week, I helped plan a peaceful demonstration against a predominantly white student organization on campus that had been misappropriating #blacklivesmatter rhetoric for their campaign. I spoke out about their decision to call Black women’s wombs hostile, and after, a reporter on the scene interviewing me asked my racial identity. No one else was singled out. Just me. Resisting the urge to shrink away, I told her, but I couldn’t help wondering: should I have worn my hair up that day?