I recently started playing This War of Mine: The Little Ones, and thus far I’ve put about 5 hours into the game. My first reaction as of now: hot, boiling tears of sadness and desperation running down my face — there may have been some snot in there too. The game is set to mirror the tragic experience of civilians during the 1992-1996 Bosnian war. Unlike most “war” centered games, you don’t play as a soldier set on a mission to snipe, kill, and destroy the “other”; you play as the “other” having to scavenge, hustle, and survive in horrid conditions, conditions my heart can’t bear to know as real.

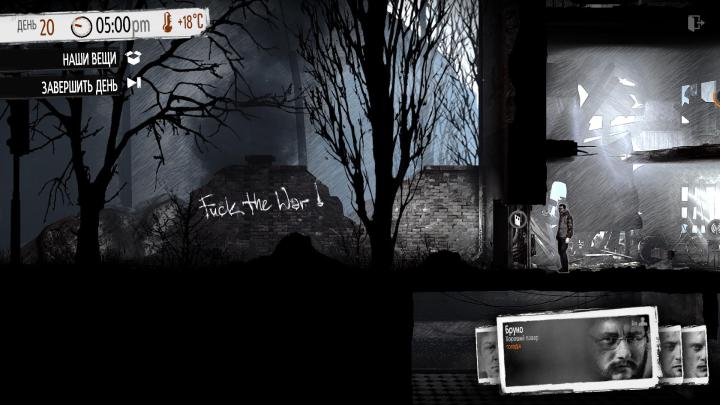

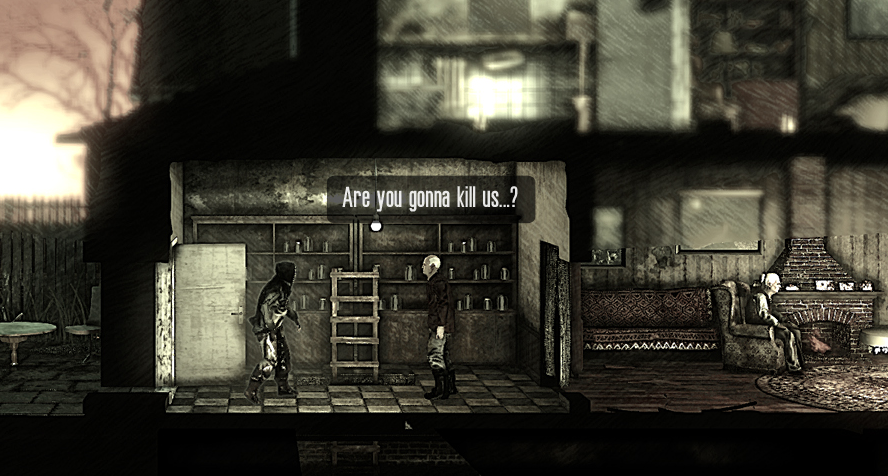

Light spoilers ahead. When I first started the game, three male characters, whom I alternate between during any session, appeared before me with an informational card. This card not only described their strengths, but what their life was like before the war. As each day passes, they journal little tidbits about how they feel, who/what they worry about, any internal conflicts they have with the methods they employ for survival, and every so often one might mention a hopeful thought or memory that keeps them trudging through the ashes and rubble of despondency. The game is set up so that you play during the day and night. The day is where you do most of your strategizing: building supplies like weapons, shovels, lock picks, radios, chairs, beds, stoves, etc. You might have a player or two sleep to rest for scavenging at night, check your rations for food and medical supplies and building supplies. Occasionally a fellow civilian will knock on your door and either ask to make a deal and trade supplies or request your help — throughout all of this, you make the decisions. When the clock strikes nightfall, you make the choice to either stay in or go and scavenge. Because supplies are always scarce, I always lean towards the scavenging end. One character goes, two stay behind; one of those two usually acts as the guard (because while you’re out raiding the living quarters of others, they, too, are out and hoping to find what will keep them alive). During one instance I went to the house of a old couple. When I entered, I noticed that they had a lot more than I did — including all of their walls being intact, a fire, blankets, food, and medicine — for a second, I paused: Do I really want to steal from these people? The man pleaded with me as his wife was sick and the medicine and food I took was vi tal to her health. Thinking of my sick friend back in our hole in the wall, I ignored the pleas, ran through the house, took all I could fit into my backpack, and went home to share the spoils with my pals. The interesting component to this game is not only does it make you grapple with your decisions, but you see the characters struggle with what they’ve done. They ask the same questions, they feel the same regret, and their guilt eats away at them until the hardness of war turns guilt into: I did what I had to do to survive. The community around you is hostile in every sense, except those that have agreed to link arms with you, those that live with you, scavenge with you, suffer with you, and ultimately die with you. All others are faces to fear.

tal to her health. Thinking of my sick friend back in our hole in the wall, I ignored the pleas, ran through the house, took all I could fit into my backpack, and went home to share the spoils with my pals. The interesting component to this game is not only does it make you grapple with your decisions, but you see the characters struggle with what they’ve done. They ask the same questions, they feel the same regret, and their guilt eats away at them until the hardness of war turns guilt into: I did what I had to do to survive. The community around you is hostile in every sense, except those that have agreed to link arms with you, those that live with you, scavenge with you, suffer with you, and ultimately die with you. All others are faces to fear.

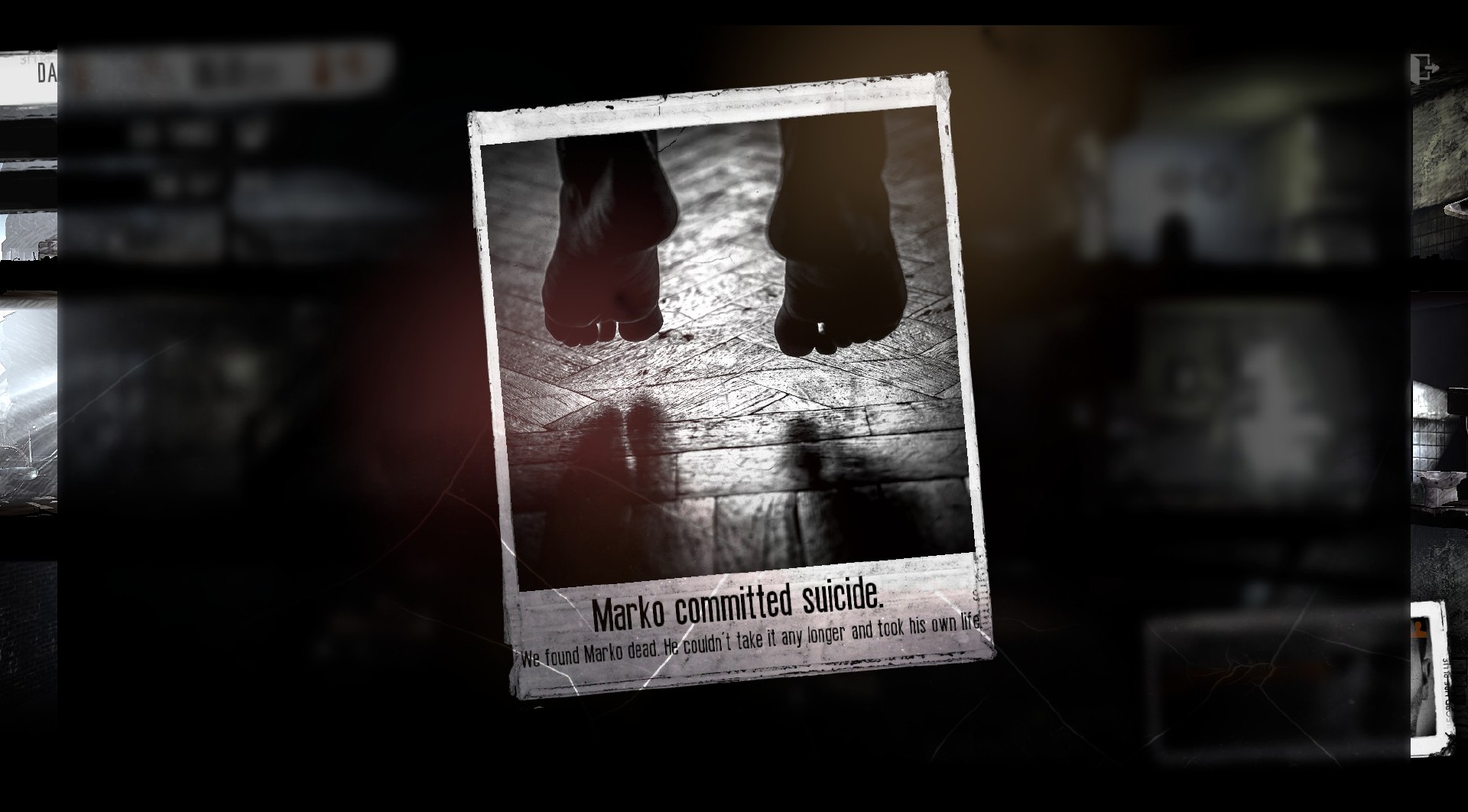

The question I keep coming to is: What are the ethics of war, particularly for those who are caught in the crossfire as innocent humans collecting teddy bears amongst trash? I, as an individual, often struggle with making sense of my ethical position: I don’t like taking from others, everyone must have equal shares, if someone has not and I have extra to spare, I give; I won’t grade a student less than they deserve if I don’t like them; I won’t take full credit for something I didn’t do alone; I won’t make my cat go longer than a day without a clean litter box or three days without changing his water. I will, however, shoot aliens without too much of a second thought in Destiny, and I will crush zombie heads with a sledge hammer and run  them over with an SUV in State of Decay while singing Destiny’s Child’s “Say My Name” without any questions regarding the ethics. Perhaps it’s because my position as the character and player have shifted drastically with this game; perhaps it’s because I have a horribly hard time understanding how this is a game. War, from this angle, feels nothing short of wretched. I have no “fun” here, I’ve no joy or sense of pleasure while playing. And it doesn’t help when the characters I play as react to this wretchedness by committing suicide. Despite all my decisions to steal, despite all my efforts to play classical music, to find books and cigarettes, to find ingredients for a hot meal, depression, despair, and utter loss takes over in a matter of days. This is the side of war no one speaks off. This is the side of war where people become monopoly pieces buried beneath the hungers of power. My heart literally aches thinking of this as someone’s lived experience.

them over with an SUV in State of Decay while singing Destiny’s Child’s “Say My Name” without any questions regarding the ethics. Perhaps it’s because my position as the character and player have shifted drastically with this game; perhaps it’s because I have a horribly hard time understanding how this is a game. War, from this angle, feels nothing short of wretched. I have no “fun” here, I’ve no joy or sense of pleasure while playing. And it doesn’t help when the characters I play as react to this wretchedness by committing suicide. Despite all my decisions to steal, despite all my efforts to play classical music, to find books and cigarettes, to find ingredients for a hot meal, depression, despair, and utter loss takes over in a matter of days. This is the side of war no one speaks off. This is the side of war where people become monopoly pieces buried beneath the hungers of power. My heart literally aches thinking of this as someone’s lived experience.

Because I’ve not put a lot of time into the game, I’ve only played as these three characters and encountered only the people I steal from or deal with. So, I’ve not played as one of the female characters or encountered a child yet — though I’m not sure I’ll be able to handle the combination of war and childhood. I was advised by a fellow Twitch follower that women have better negotiating skills (sometimes you run into people like snipers or other desperate folk who attempt to kill you). I’m currently down to one player, and his hope is waning to the point that I fear another suicide snapshot will emerge on my screen. I make an effort to not read about the game or watch others play, so I’m not sure if I can make friends or build a new community. As of right now, I’m on my own hoping to make it another night, another day alive. I keep asking myself why I keep attempting to play, and the only plausible conclusion I can draw comes from my desperation to see the end of war.