The past couple weeks, I’ve written about patriarchal constructions of fathers and daughters in The Last of Us and Rise of the Tomb Raider, and I wanted to spend some time this week wrapping up these assorted musings. My last two posts have worked to put these two games in conversation with each other by examining some of the similarities in the ways each game represents fatherhood and daughterhood, but this week I want to examine some of the differences in such representations, especially the differences in the ways Ellie and Lara are constructed—because I think that by working to understand the differences, we might more fully unpack how it is The Last of Us and Rise of the Tomb Raider perpetuate patriarchal configurations of kinship ties.

In the case of Ellie, I think it’s important to note that we get the chance to play her only in the penultimate chapter of the game; as such, for most of the game (that is, in all but this chapter), Ellie is what Maddy Myers calls a “package quest”—she is something that “must be delivered in order to obtain a reward necessary for you to survive.” But when the game shifts, when it allows us to play Ellie, it seems to be working to complicate this characterization by embarking on a sort of coming of age story of sorts, a Bildungsroman. As such, there is an interplay here between the game’s mechanics and its narrative—we play Ellie, we act through her, when she begins to come into her own, when she gets to act and gain agency. But this Bildungsroman is problematic for a couple reasons. First, Ellie’s coming of age is still framed as being a result of her role as a daughter figure; that is, she must come of age, she must grow up, she must act because Joel can’t, because he is gravely injured, because she must do everything she can to save him. In this way, her Bildungsroman operates in service of the father and as something that strengthens her kinship ties with Joel. But more than that, her coming of age is also sexualized through the invocation of rape. Indeed, as Mattie Brice puts it,

In the case of Ellie, I think it’s important to note that we get the chance to play her only in the penultimate chapter of the game; as such, for most of the game (that is, in all but this chapter), Ellie is what Maddy Myers calls a “package quest”—she is something that “must be delivered in order to obtain a reward necessary for you to survive.” But when the game shifts, when it allows us to play Ellie, it seems to be working to complicate this characterization by embarking on a sort of coming of age story of sorts, a Bildungsroman. As such, there is an interplay here between the game’s mechanics and its narrative—we play Ellie, we act through her, when she begins to come into her own, when she gets to act and gain agency. But this Bildungsroman is problematic for a couple reasons. First, Ellie’s coming of age is still framed as being a result of her role as a daughter figure; that is, she must come of age, she must grow up, she must act because Joel can’t, because he is gravely injured, because she must do everything she can to save him. In this way, her Bildungsroman operates in service of the father and as something that strengthens her kinship ties with Joel. But more than that, her coming of age is also sexualized through the invocation of rape. Indeed, as Mattie Brice puts it,

[Ellie’s] identity-specific drama is surrounded by rape imagery and the actual threat of rape, because right now that seems to be the main way developers get drama out of their women characters. We don’t end Ellie’s chapter with a new insight really, because we always knew she could take care of herself. This makes Joel’s intrusion to the scene even more bitter because you know the game is going back to focus on him just after a girl survived attempted rape.

And as a result of this immediate shift back to playing Joel after this attempted rape, Brice argues that such a shift ultimately serves “as a bonding moment to further Joel’s character arch.” While the scene does seem to work to further Joel’s character development, it also works to further Ellie’s, and the problem with this is that her coming of age (as is often the case in the ways young women’s stories are told) is framed in a sexualized way. And Joel’s investment in her, as her father figure, is solidified through such framing. Their kinship is solidified through such framing.

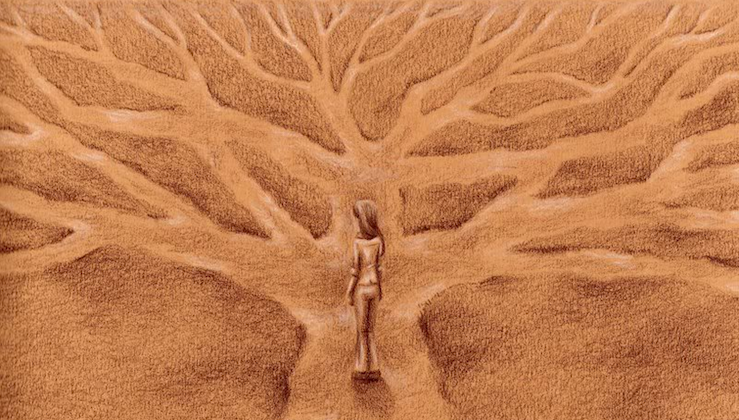

Such framing isn’t necessarily the case in Rise of the Tomb Raider (although a case can be made for the argument that such a sexualized Bildungsroman does occur in the game’s prequel). And while we only play  Ellie for a short amount of time in The Last of Us, we play Lara Croft for the entirety of Rise of the Tomb Raider. Further, Lara Croft, unlike Ellie, is an adult—one who has supposedly already come of age in the previous game—who claims she does what she does because she wants her choices to “make a difference.” This emphasis on her choices and the motivation behind her actions seems to be mirrored in the mechanics that are at play in the fight sequences of the game, for we can choose to go about such sequences in one of two ways; that is, we can choose to either make use of stealth, hiding in bushes and quietly disposing of our enemies, or to go into the fight head first, guns blazing. Yet, the ability to make such choices in our gameplay only goes so far, for regardless of which tactics we decide to use, the results are the same and the game moves forward in a linear way. And this illusion of choice also seems to mirror the illusion that Lara is making these choices for herself—for instead of wanting to “make a difference” solely because that’s what she wants to do, she ultimately wants to make a difference in order to make her father proud, to prove him right, to prove that he did not die in vain and that, as Lara puts it, “he died for something.” Thus, Lara’s choices throughout the game operate not in service of herself but in service of her father. This, then, highlights the fact that such kinship ties are underscored as being integral to Lara’s identity–her ties to her father, her daughterhood, significantly impact the choices she makes.

Ellie for a short amount of time in The Last of Us, we play Lara Croft for the entirety of Rise of the Tomb Raider. Further, Lara Croft, unlike Ellie, is an adult—one who has supposedly already come of age in the previous game—who claims she does what she does because she wants her choices to “make a difference.” This emphasis on her choices and the motivation behind her actions seems to be mirrored in the mechanics that are at play in the fight sequences of the game, for we can choose to go about such sequences in one of two ways; that is, we can choose to either make use of stealth, hiding in bushes and quietly disposing of our enemies, or to go into the fight head first, guns blazing. Yet, the ability to make such choices in our gameplay only goes so far, for regardless of which tactics we decide to use, the results are the same and the game moves forward in a linear way. And this illusion of choice also seems to mirror the illusion that Lara is making these choices for herself—for instead of wanting to “make a difference” solely because that’s what she wants to do, she ultimately wants to make a difference in order to make her father proud, to prove him right, to prove that he did not die in vain and that, as Lara puts it, “he died for something.” Thus, Lara’s choices throughout the game operate not in service of herself but in service of her father. This, then, highlights the fact that such kinship ties are underscored as being integral to Lara’s identity–her ties to her father, her daughterhood, significantly impact the choices she makes.

This is all to say that what all this seems to come down to for both Ellie and Lara is the significance of kinship ties and how such kinship results in patriarchal, gendered identity formation—these women are highlighted as being primarily daughters of men. And the patriarchal configurations of kinship in these two games speaks to the idea that, as Keith Stuart puts it, “although narrative themes have progressed, the games industry is still heavily reliant on the old themes of power, authority and physical force.” These themes of power and authority in games is especially rendered across gendered lines, as evidenced by the paternalistic, patriarchal power wielded by the father figures in Rise of the Tomb Raider and The Last of Us. However, it also seems important to note that such patriarchal representations of fatherhood and daughterhood are not unique to game narratives. And because such representational violences are not unique to video games or the gaming industry, the treatment of games as an isolated, separate space limits us from thinking about the overall implications of how it is such representations occur across media forms—in other words, it prevents us from fully understanding how institutionalized systems of oppression and power are perpetuated through a variety of mediums. Since such violences are not unique to games, perhaps our critique of them can allow us to further understand how gendered representational violences—violences like those portrayed through the father-daughter configurations of The Last of Us and Rise of the Tomb Raider—are repeated across representational and narrative forms as well as how these patterns of representation work to perpetuate gendered institutions of power, like that of patriarchy’s power of the father.