I’ve been thinking a lot about the continued impacts of GamerGate lately, though not perhaps in the larger sense of wondering what it all means, but how it jibes with my experience with and in gaming media. While it’s been several years since I did any writing about games outside of this site, which obviously takes a different approach from traditional notions of game blogging, reporting, and reviewing, I still have a lot of friends who work in gaming media, and I read gaming sites, and because of that, something’s been nagging at me. It’s this idea of “ethics,” and not because I want to argue that GamerGate is not about ethics in journalism or really anything else, like harassment, but because I want to explore gaming media from the point of view of someone who worked there several years ago and who still keeps up. Why? Because I have come to the conclusion that I don’t think we can even have a real conversation about ethics at all in gaming media, at least, not without deeply exploring that very sphere, thinking about what’s required and how it’s changed and is changing, and how we look at creators of all types.

The necessity of interaction

In order to effectively know games, the people who write about them have to play them. Hands-on experience is part of the package; you can’t effectively review a game, after all, without experiencing the mechanics. Book reviewers need to read, film and television critics need to watch, and members of the gaming media need to play, and in this way, they build preferences. Some film critics approach all action films with a raised eyebrow; some game reviewers approach survival horror with trepidation beyond concern for jump scares. This is not only natural, but also the foundation of the reviewer-reader relationship; readers find those reviewers or outlets with opinions that most often align with their own, and these are the reviewers they trust.

Reporting, in general, is different. When it’s a matter of news, we call for objectivity. Just the facts. Yesterday, a building burned down. No one was injured. No one yet knows what caused the fire. This politician spoke. Here’s what they said, and to whom, and we’ll leave opinions out of it.

But the wider audience of gaming enthusiasts has rarely asked for news to be stripped down in this way. Sure, tell us about the release date and the publisher, but drop in a joke or two, and when you have the screenshots or the first video, describe it. Embed opinion. In this way, the web of opinion, of micro- and pre-reviewing has spread throughout the history of writing about games. While with other types of media, there are strict news feeds, and plenty of them – here’s this new film, and its stars; so-and-so has announced a new book on this date – we rarely see them for games, and there doesn’t seem to be much call for them. We want hype trains; give us hype trains and theories and ideas and previews and analysis based on past development.

Why the difference? Part of this is due to that need to play; effective members of the gaming press are then often as much enthusiasts as their readers. It’s how they come to this particular media sphere instead of another. Watching and reading are primarily passive activities, after all; to engage is to receive information. So film critics don’t need to make movies, and book reviewers don’t necessarily have to write books. But playing is interactive. Maybe members of the gaming press aren’t making games (though many are, or move on to that!), but in order to be effective, they can’t just watch. They have to play. In fact, writers and reporters accused of relying on video or Let’s Plays instead of actually playing are looked upon with derision. The only way, then, to be a successful writer in the media sphere is to participate. But if a writer seems to prefer one game style or system too much — apart from that necessary development of preference mentioned above — they’re labeled a fanboy or “stan.” Fine lines. Traps everywhere.

Another part, perhaps, is also due to the way the gaming press receives information, both currently and historically. When I was actively working in that sphere, we got press releases and direct information, certainly, but a great deal of content was also sourced from Japanese publications, from forums, and from other sites – reblogging, and adding a site’s own spin – was a common practice, and it still happens. There’s only so much actual news, after all, and most outlets want to have the same basic information available. If it’s not on your site, some other site is getting the traffic when the audience has to leave to search elsewhere. In recent years, there’s been more content creation in the form of videos, video reviews, podcasts, and longform exploratory pieces, which is wonderful, but little seems to have changed when it comes to actual news reportage, except that perhaps there’s less of it. What’s still the same is the injection of personality, which leads to another issue that is, if not unique to gaming media, is perhaps more embedded than in other types of media: personality and credibility.

Gamer “cred” is an issue much discussed here, and one I won’t rehash unnecessarily, but the enthusiast community has always had various yardsticks by which they measure just how much of a “real” gamer someone is. I personally don’t see this a lot on other enthusiast media or in other fandoms (I’m not saying it doesn’t exist). Comments on football analysis in my experience are not much littered with accusations that the writer is not a real sports fan, and I don’t see a lot of yelling at film critics for not really watching movies, but it happens in spades in the gaming media. So we’re back to the necessity of participating, but not just with the games themselves, but with the fandom communities. Mingling at conventions, playing online with site loyalists, sharing information about gamer tags and network IDs, and participating in forums and on social media have long been ways for members of the gaming press to “get out there” and engage. But now, there are invisible lines drawn everywhere. Engage, but not too much. Go to trade shows and cons, but don’t get too friendly with developers or other industry people. In such an insular industry, what’s a writer to do?

Personality factors into this, too. In those engagements, and in the writing itself, the gaming media is expected to entertain. Write a story in a flat tone and negative comments pour in. Be funny, then, but not too funny. Be an enthusiast and play, but don’t develop fandoms that might prevent you from being objective. Play these games, and well, but don’t be into any of them.

It’s a nightmare. I’d never go back to it, not for a second. I’ll be over here, researching and studying.

But what about ethics?

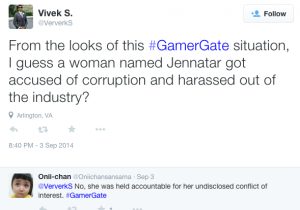

The Jenn Frank debacle is a great, if tragic, example. Frank wrote an op/ed for The Guardian in the early days of GamerGate addressing harassment of women in gaming, in which she talked about recent campaigns of harassment and confessed her own overpowering fears of dealing with similar issues. Almost immediately, her fears were realized when the accusations of corruption spread through the digital sphere.

Apparently, Frank had added a footnote to the original indicating she had met Anita Sarkeesian, whom she discusses in the article, and disclosing she “had purchased and is a supporter of Zoe Quinn’s work.” The footnote was cut from the original published copy by editors at The Guardian because it didn’t meet their standards for necessary disclosure of personal connections (meaning the connection was too tenuous), but the piece was later edited on-site, at Frank’s request, after reports of her “conflict of interest” hit Twitter and she was targeted with questions and mentions detailing her corruption. Frank later announced she was quitting the industry.

This is important not because Frank was harassed (that’s always important, but these days, it’s an expected reality), but because of the vast divide between what vocal GamerGaters considered a conflict of interest (and evidence of “corruption”) and what the editorial and legal teams at The Guardian considered corruption. I apologize for the amount of quotation marks I’m about to use, but bear with me here: this is a clear example of vocal GamerGate supporters “investigating” and revealing “corruption” in gaming media. Except it’s not investigating, but rather comparing Patreon donor lists and revealing that people in arts and related fields support each other, and it’s not “corruption” except to those who have simply decided to call it corruption. In short, we have a group of people calling themselves consumer watchdogs who don’t know what they’re watching for watching people who may have various levels of training, writing for various outlets that have different standards, and everyone is trying to apply some moving goalpost. It’s not effective. It’s possibly not even reasonable.

This is important not because Frank was harassed (that’s always important, but these days, it’s an expected reality), but because of the vast divide between what vocal GamerGaters considered a conflict of interest (and evidence of “corruption”) and what the editorial and legal teams at The Guardian considered corruption. I apologize for the amount of quotation marks I’m about to use, but bear with me here: this is a clear example of vocal GamerGate supporters “investigating” and revealing “corruption” in gaming media. Except it’s not investigating, but rather comparing Patreon donor lists and revealing that people in arts and related fields support each other, and it’s not “corruption” except to those who have simply decided to call it corruption. In short, we have a group of people calling themselves consumer watchdogs who don’t know what they’re watching for watching people who may have various levels of training, writing for various outlets that have different standards, and everyone is trying to apply some moving goalpost. It’s not effective. It’s possibly not even reasonable.

False information spreads, too, like wildfire, as here, when a Twitter user praises the Guardian for “firing” Jenn Frank in their effort to weed out corruption. The loudest, it seems, don’t know much of anything, but they’re happy to talk about it, and talk, and talk more.

In real journalism, when you are in bed with those you write about you get fired. Well done @guardian for weeding out corruption @jennatar

— Herschel (@Roth4Israel) September 4, 2014

And it’s not just this one example. Any time some alleged corruption surfaced, pro-GG sites and social media accounts converged on the targets, and a cursory glance at the subreddit Kotaku in Action reveals that this kind of thing is still a healthy practice, with users working overtime to try to catch gaming sites in corrupt acts. Just the other day, I glanced over to find redditors yelling about an IGN piece crossposted on the PlayStation blog. It was clearly identified as a crosspost, and yet some posters were arguing that the “conflict of interest” wasn’t disclosed. Some of the comments on the PS blog post are also in this vein, but I’d argue that the official PlayStation blog is hardly likely to be a hub of journalism in the first place.

And while we’re talking about journalism, an interview with Dr. Greg Lisby, professor of Communication at Georgia State, is often linked as “proof” of corruption in gaming media. He’s certainly very clear about what is and isn’t a breach of ethics in the sense of traditional journalism. But what about games media falls within that? Dr. Lisby says at one point, “[The journalist’s] obligation is to write truth that is newsworthy.” Is that what we ask of the people who write about games? Yes, but is it all we ask of them? He also addresses opinion pieces and the importance of disclosure in order to maintain trust with the audience, and I’ll agree there without question — there should be disclosure, but at what level? The Guardian didn’t think it mattered that Jenn Frank supported Zoe Quinn’s Patreon. Where then do we draw lines? “I was paid by Microsoft to write a good review” would be a clear breach. Even Lisby was less clear about friends in the industry, and when asked about supporting creators, he described what sounded like a more traditional investment scenario in which both parties benefit, whereas if a member of the gaming media backs a Kickstarter for a project, they get… a game, and maybe some swag (that they paid for). That’s less beneficial to the writer than the developer sending them a free copy of the game — which does happen, and frequently.

But all this discussion is murkier still when we look at various aspects of the gaming media. For one, only some writers out there in the larger sphere are even educated as journalists or writers. Some have degrees or even advanced degrees in journalism or new media or communications, while others are simply enthusiasts who can write. Publications may or may not fact check or even have much of an editorial process. Why? Because gaming media is, by and large, more easily classified as an entertainment industry than one couched firmly in journalism. There are overlaps, and with longer, more investigative pieces more traditional considerations may apply, but taking traditional news ethics and practices and trying to apply them to gaming media seems a poor notion. I’m not saying that these writers should all necessarily have the same background and training, or that there should be one blanket standard that covers sites that take a variety of approaches. I’m simply saying that assuming they do is complicating the issue further.

This is also not to say that the games media shouldn’t have ethical practices, but rather to say that since its inception, gaming media has never stopped changing. Games themselves change too quickly, and the media in all forms has been shifting rapidly over the past three decades. I’ve compiled some information here, an amalgamation of what I experienced when I was writing gaming coverage, along with what I found when I spoke to some friends about standards and practices at current outlets, and what I discovered from friends who write for traditional media — newspapers and major news magazines, online and in print.

When I was writing for Joystiq satellite sites in particular, and also for smaller sites, there was little training. Joystiq had a basic style guide and some information about best practices, and as an editor, I hired new writers based on personality, knowledge, and writing ability. They were offered some guidance, but we looked for self-starters. Average pieces were not much edited and not fact-checked. Columns were edited. At the smaller sites I wrote for, there was nothing. No guides and no training outside of ideas about post-tagging and categorization.

Friends who are currently or who were until recently active participants in gaming media reported that fact-checking has become more common, but isn’t always a regular practice. One friend said it varied widely site-to-site (and this particular friend has written for everyone), but on average, reported that daily, regular reports may see one writer checking for another writer, but any editing was usually reserved for columns or freelance features. Even then fact-checking and editing wasn’t “standard.” This seems to me to be indicative of more a community built on trust than hard journalism. Enthusiasts and cultural critics writing about things they know about. Whether or not that’d disconnecting from the audience is another issue; what should and should not also then be disclosed, too, is something that requires thoughtful discussion, something I’m guessing is welcomed more than the kind of run-and-gun armchair watchdoggery afforded by Twitter and pop-up sites that “reveal corruption” that isn’t hidden at all.

(I may have some opinions about some of this. I don’t pretend to be objective, just interested.)

Interestingly, when I spoke to friends who write for larger, more traditional outlets, they reported that at some sites, copyeditors were no longer employed and fact-checking and editorial checks on personal essays and opinion pieces, at least, was not as common as one might expect. Some outlets were very rigorous, with strict editorial policies and processes, but things overall are changing. My guess this is partly due to costs and partly due to the popularity of blogs, opinion, nonfiction, etc., but I’m no expert.

Finally, it’s important to note that many gaming media sites self-identify as blogs or “gaming destinations” at least do not declare themselves hard news organizations; they do not always post strict editorial guidelines and policies (though in the wake of GamerGate, that’s changing), whereas many newspapers and news media organizations do. The difference here is key, I think, and supports the idea of games media as more entertainment than anything else. I don’t mean to undermine the work done in games media; again, I did it, I know it, and it’s never as fun as one would think it might be. “But you write about games all day!” Yes, and are often decried for it, paid less than you probably deserve, all while fighting for access and clicks. Still, the changes in games media and the changes in traditional news media are leading to a potential convergence wherein the one has stricter standards and the other relaxes a bit. Media is in flux. It’s hard to make concrete statements about any of it, and for games media, it’s been that way as long as they’ve existed.

Patreon, Kickstarter, and “incest” in creator communities

“I’m starting to feel like Patreon is a poison.” I keep seeing this sentiment, or one like it, popping up in discussion threads and long webs of conversation about so-called corruption, and as I researched this piece, I kept circling back around to the idea of it. Patreon as poison? It’s difficult for me to see Patreon and other sites that support creators and creations as anything other than a blessing.

Then again, I’m a writer, in the creative sense, with far-reaching ties in a number of writing communities. I’m in dozens of writers’ groups, I attend a huge yearly conference, I trade work with writers from all over the world, and I support a number of literary journals, some of which have published my work (and some I hope to break into in the future). But more than that, the individuals in this community support each other. We buy each others’ books; we share and support Kickstarters; we tweet news and reviews, and we contribute by entering contests at journals and presses where our friends are on staff. Sure, we hope to win, but we also want to see the magazines and presses stay in business. That’s how we help sustain the industry.

So when I see people crowing about collusion because a writer supported another writer’s Patreon, I have a hard time understanding the problem. Polygon’s Ben Kuchera supports a number of Patreons, some game-related and some not. Jenn Frank did (and does?), and that was at the center of charges of corruption. Patreon and Kickstarter became such an issue that some gaming sites changed their policies to address what was and wasn’t okay in terms of support. I think that’s great – writers who are working for an entity should have rules and boundaries, and their audiences should know about them, particular in terms of support of developers they may end up reviewing. Full disclosure, which sites like Patreon already provide when revealing donor lists. But I have a hard time seeing a few dollars thrown around amongst friends doing the same thing – writers supporting writers – as any kind of an issue. It’s standard, and it happened long before Patreon’s rise to prominence. If you’re a writer, you’re usually also a reader, and you want the other writers you like to keep going.

Lest I be accused of fallacy here in arguing tradition for tradition’s sake, though, let me clarify: I think artists and creators support other artists and creators because we understand the terror and hardship that comes with not always knowing where the next paycheck will come from, and because we know the struggle of creating good content is real. It’s already hard enough for creators to get paid in some instances. Why make it harder?

In closing

I lied. I said I wouldn’t speak about harassment at the center of GamerGate, but it’s hard not to. Sure, I think discussions of ethics are important, but I think it’s also important first to explore and define gaming media, to determine what we want from it, to decide if we’re looking at news or cultural criticism or fan engagement, or some strange Venn diagram that includes all of the above at various levels on various sites. We have to define it, and keep it steady for a while, and figure out new ethical lines, not simply pull standards at random, and that sort of work is hard. It probably can’t be done on Twitter, and it can’t be done in the midst of angry campaigns of harassment. As part of this, I re-read the Newsweek article that reported on GamerGame tweets to journalists and developers, looking for positive and negative content, but it felt unsatisfying somehow, so I did a few searches of my own, just out of curiosity. I looked particularly at Nathan Grayson and Zoe Quinn, with their situation being at the genesis of the whole mess, and used various tweet archival platforms to look at mentions of rape along with their usernames. For Quinn, the count was 1280 consistently; for Grayson, 26.

I sat for a long time, looking at my screen, wondering what this meant. Sure, a culture of sexual violence and misogyny reserved for women; I wrote about that recently. But that, combined with abhorrent statements like, “If only Zoe Quinn had kept her legs shut, we wouldn’t be here!”, really does make me wonder if ethics wasn’t always a secondary consideration. At the end of the day, I have such a hard time seeing things any other way.