I recently read a great article from FemHype that focused on the problematic, one dimensional representation of mentally ill characters in video games. Lindsay Goto, author of the article, analyzed the insanity trope in depth, writing about the portrayal of mentally ill characters as either crazed antagonists with a violent agenda or a babbling, nonsensical person bound in a straightjacket. These exaggerated representations not only reinforce the idea that mentally ill characters are incomplete and unable to blend into society, but are also somewhat cartoonish. Though straightjackets were once used in mental hospitals and fantasies of grandiose violence are a thing, there are so many varying degrees of mental illness and a world of nuance that most games fail to show or dig into, relying instead on painting extremist portraits described by insanity tropes. One can argue that these tropes stray from a variety of other representations. I was so moved and inspired by Goto’s article that I decided to write a response post on Not Your Mama’s Gamer. Let me tell you why I was so moved.

First of all, I’m not an expert on mental illness. There are people who have it worse than me but I do have an anxiety disorder. It runs in my family. I’m very fearful of specific situations and I’m rather fond of being in control. It’s irrational. It sucks, but it doesn’t define me. I’m able to work, have a social life, and so on. Mental illness is tricky in that there’s nothing to indicate something’s off. There’s no visual cue. I was originally drawn to Goto’s article because of my own experiences with anxiety. Like Goto, I’d like to see better or more unique representations of mentally ill characters. There needs to be more consideration in regards to how complex mental illnesses really are. This line of thinking may help create better, fresher, more interesting games with more nuance.

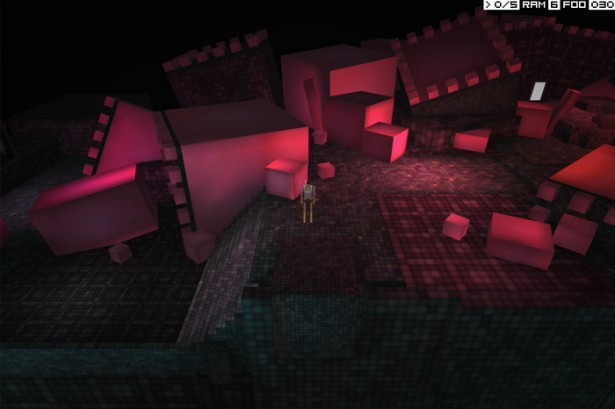

A couple of weeks ago I played a game called Neverending Nightmares. The game follows Thomas, the pajama clad protagonist, through a series of nightmares he’s unable to wake from. It chronicles his deteriorating mental state. When the player completes each chapter or segment, the protagonist’s reality alters. There’s also a plethora of ruin imagery I’ll later delve into. I wanted more than anything to like this game. There were aspects of the game I really enjoyed but it fell short for me as a whole. I researched the developers’ Kickstarter page and was thrilled by what I discovered. Matt Gilgenbach, the game’s creative director, revealed that he suffered from obsessive compulsive disorder and depression. He went on to say that the game was inspired by his personal experiences with mental illness. I expected this game to disassemble the insanity trope. I also felt as though I could invest more trust in this kind of game knowing that one of the developers had first-hand experience with mental illness.

Neverending Nightmares has all the markers of a classic horror game: jump scares, a creepy environment, and a mentally unstable protagonist. It’s not at all uncommon to see the representation of mentally ill characters in horror. Though mental illness can indeed change a person’s perception of the world, it isn’t a death sentence and there are moments of genuine clarity. His mental state worsens throughout the length of the game. However, the game seems to lean on his episodes for jump scares and violent or graphic imagery. Thomas is more like the vessel for the horror elements of the game. It’s perfectly acceptable to explore mental illness in a horror framework but there needs to be more depth to the afflicted character. I want Thomas to tell me how he manages his mental illness. I want to be educated. Not every mentally ill person suffers the same way but Thomas falls into the common traps of the insanity trope. He’s violent towards himself and others. There are two instances in which he stabs a young girl in the stomach and pulls a vein out of his own arm. Just because he’s mentally ill doesn’t mean he’s necessarily violent. Though these scenes might very well be hallucinations, it all seems overblown for the sake of being overblown. I want to know why he’s doing these things. Was he sexually abused? Does he suffer from a particular disorder? Is it just genetic?

Neverending Nightmares has all the markers of a classic horror game: jump scares, a creepy environment, and a mentally unstable protagonist. It’s not at all uncommon to see the representation of mentally ill characters in horror. Though mental illness can indeed change a person’s perception of the world, it isn’t a death sentence and there are moments of genuine clarity. His mental state worsens throughout the length of the game. However, the game seems to lean on his episodes for jump scares and violent or graphic imagery. Thomas is more like the vessel for the horror elements of the game. It’s perfectly acceptable to explore mental illness in a horror framework but there needs to be more depth to the afflicted character. I want Thomas to tell me how he manages his mental illness. I want to be educated. Not every mentally ill person suffers the same way but Thomas falls into the common traps of the insanity trope. He’s violent towards himself and others. There are two instances in which he stabs a young girl in the stomach and pulls a vein out of his own arm. Just because he’s mentally ill doesn’t mean he’s necessarily violent. Though these scenes might very well be hallucinations, it all seems overblown for the sake of being overblown. I want to know why he’s doing these things. Was he sexually abused? Does he suffer from a particular disorder? Is it just genetic?

I did like the  way in which Thomas’ shaky mental state manifests itself. The mansion is his prison. It serves as the physical embodiment of his psychosis. This is where the ruin imagery comes into play. As Thomas’ mental state goes downhill, the wallpaper peels and the portraits tilt. The house itself is something of a character with its own narrative. I appreciate stories where storms, houses, and other non-human entities are characterized. Though Thomas’ mental state is intertwined with the state of the house, the two are separate in that they’re telling (or not telling) two different stories. Aside from the fact that Thomas is mentally unstable, I know next to nothing about him. The storyline is purposefully not linear and the character of Gabby often changes roles throughout the course of the game. He is defined by his mental illness and that ultimately makes him unreliable and untrustworthy. The house, however, is more telling. The player is given access into specific rooms. The house, though voiceless, allows the player to imagine and wonder. Who’s the family in that portrait? Why is there a room filled with dolls? Perhaps it’s not that the house is more telling. Perhaps the house is more reliable as a character.

way in which Thomas’ shaky mental state manifests itself. The mansion is his prison. It serves as the physical embodiment of his psychosis. This is where the ruin imagery comes into play. As Thomas’ mental state goes downhill, the wallpaper peels and the portraits tilt. The house itself is something of a character with its own narrative. I appreciate stories where storms, houses, and other non-human entities are characterized. Though Thomas’ mental state is intertwined with the state of the house, the two are separate in that they’re telling (or not telling) two different stories. Aside from the fact that Thomas is mentally unstable, I know next to nothing about him. The storyline is purposefully not linear and the character of Gabby often changes roles throughout the course of the game. He is defined by his mental illness and that ultimately makes him unreliable and untrustworthy. The house, however, is more telling. The player is given access into specific rooms. The house, though voiceless, allows the player to imagine and wonder. Who’s the family in that portrait? Why is there a room filled with dolls? Perhaps it’s not that the house is more telling. Perhaps the house is more reliable as a character.

Additionally, Thomas doesn’t have very strong reactions to his disturbing hallucinations. His facial expressions are fairly neutral for the most part. We would be able to better read his lack of facial expression if there were more cues on how to read Thomas himself. Again, does he suffer from an addiction? What is his disorder? I’m not sure if it’s because of the limitations of the artwork or not but he appeared to be only slightly apprehensive at certain points. It felt as though he was disconnected from his own psychotic episodes. Perhaps that’s the point. It was a challenge for me to relate to Thomas.

Though I personally wasn’t swayed by Neverending Nightmares, there are a handful of games out there that handle mental illness in different ways. Zoe Quinn’s Depression Quest is a text based game that situates the player in realistic social situations. There’s even a warning at the beginning of the game that states it may trigger depressive feelings. Freebird Games’ To The Moon is another unique example because it’s implied that Johnny’s mother is mentally unstable. This aspect speaks to the reality of how many mentally ill people go undiagnosed.

Mental illness doesn’t have to define a character or person. The mentally ill aren’t always violent or unreliable. Above all, mental illness doesn’t equal incompleteness. It would be refreshing to see more diverse representations of mentally ill characters in video games.