Last week, I wrote about a game called Pony Island and the manner in which the game makes use of metanarrativity. And I also mentioned that my interest in such a narrative technique stems from my location as a literary studies scholar—an interest that has extended my consideration of such techniques to other games as well, to a consideration of how and why various games make use of metafiction, and to a consideration of why it is such meta moves matter.

Last week, I wrote about a game called Pony Island and the manner in which the game makes use of metanarrativity. And I also mentioned that my interest in such a narrative technique stems from my location as a literary studies scholar—an interest that has extended my consideration of such techniques to other games as well, to a consideration of how and why various games make use of metafiction, and to a consideration of why it is such meta moves matter.

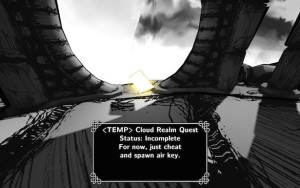

Perhaps one of the reasons I’m lingering on this is the fact that I’ll be presenting a paper on the metanarrativity of The Magic Circle at a literature conference this week, so this subject matter is very much on my mind at the moment. Indeed, Jake Muncy (whom I also mentioned last week in my discussion of Pony Island) describes The Magic Circle as a game about a “fake game” that is “stuck in development hell. Players must ‘hack’ the AI and create something coherent from its scattered pieces.” And as we work to create such coherence, Muncy continues, we engage with the game’s story and critique: “The Magic Circle’s story, in which we hear its fictitious ‘designers’ as they bicker over the game’s direction, is shot through with concerns about the rules and challenges that come with designing games for a mass audience. How does the art we love actually impact the people who slaved away to make it? It can be difficult to see creators as people.” But the game doesn’t simply explore the role of creators—because it seems just as slippery to engage with the role of players as well; and, as a result, Muncy quotes Jordan Thomas, the creator of The Magic Circle, as saying,

“My whole career, I had heard players refer to big-name-big-face developers as ‘gods,’” Thomas says. “But when I actually broke into the industry, I realized that the inverse was also true. Developers spoke about the players with a vehement surety that they knew what the player wanted, and because the player is such a broad field—it could be anybody—they argued about that unknown like a deity… in the Second Coming sense. ‘When the player shows up, they’re not going to care about that.’”

Thus, by working to explore the roles of and relationships between players and developers, the game “is about removing that veil, forcing the two parties to reckon with each other as not distant, unknowable obscurities, but as people.” And the game seems to work to remove this veil, especially, through its metafictional setting–through the fact that it’s a game about the process of making and playing games.

Thus, by working to explore the roles of and relationships between players and developers, the game “is about removing that veil, forcing the two parties to reckon with each other as not distant, unknowable obscurities, but as people.” And the game seems to work to remove this veil, especially, through its metafictional setting–through the fact that it’s a game about the process of making and playing games.

I also thought about the idea of metanarrativity while I streamed Until Dawn this past weekend for our 24 hour streaming Mammothon. It’s another game that has some pretty metafictional moments, or as Dean Takahashi puts it, “There’s a meta layer in the story where an analyst starts questioning you, the player, about how you think the ‘game’ is going. The conversations with the analyst are just one part where you realize that nothing is as it seems on the mountain.” Such moments make us, the players, more aware of our roles, more aware of the choices we make, and more aware of the parts we ourselves play in the ways we interact with games. And perhaps such an awareness is meant to have us think more critically about how and why we play games.

I also thought about the idea of metanarrativity while I streamed Until Dawn this past weekend for our 24 hour streaming Mammothon. It’s another game that has some pretty metafictional moments, or as Dean Takahashi puts it, “There’s a meta layer in the story where an analyst starts questioning you, the player, about how you think the ‘game’ is going. The conversations with the analyst are just one part where you realize that nothing is as it seems on the mountain.” Such moments make us, the players, more aware of our roles, more aware of the choices we make, and more aware of the parts we ourselves play in the ways we interact with games. And perhaps such an awareness is meant to have us think more critically about how and why we play games.

This sort of critical awareness that results from our engagement with metafictional media and narrative forms brings to mind, for me, Linda Hutcheon’s discussion of postmodernism in The Politics of Postmodernism. I’ve talked a bit about Hutcheon’s arguments before, but to summarize, Linda Hutcheon defines the postmodern text, ultimately, as a form of “paradoxically complicitous critique.” And this critique is, paradoxically, complicitous because, while such postmodern forms allow us to consider the construction of self and the systems of power in which the self is entrenched in often self-reflexive and metafictional ways, it would also seem that such meaning-making is indeed paradoxical because it both inscribes and subverts these systems at the same time. Through this characterization of postmodernism as paradoxically complicitous critique, Hutcheon, then, works to frame such texts as having the potential for productive complexity in representing our social structures and construction of self.

Thus, the postmodern paradoxically complicitous critique of the kind of metanarrativity that we see in games like Pony Island or The Magic Circle or Until Dawn reminds us of the fact that our new and emerging narrative forms (like video games) have the ability to enact similarly significant commentaries on our systems of representation as our older or more so-called “traditional” forms do. But it should also be said that video games cause us to think about such systems of representation in a somewhat different way. Because video games allow us to think not only about how representations might occur differently in our texts but also about how we, as scholars and players and everything in between, might talk about such representations differently when exploring other narrative forms as well.

Yet, while it is important to highlight where it is our narratives and scholarship are going in regards to the emerging form of video games, it is also important to note the heritage from whence such narratives came. In other words, it is important for us to consider, for instance, the manner in which postmodern structures have affected the ways that video game narratives are structured. And video games like Pony Island, The Magic Circle, and Until Dawn, it would seem, tell the types of stories that, although different in structure and form than other more “traditional” types of texts, have the potential to utilize, for one, a postmodern focus to alert us to the systems of meaning in which we are located. Thus, video games, too, of course, have the potential to make meaning.

Yet, while it is important to highlight where it is our narratives and scholarship are going in regards to the emerging form of video games, it is also important to note the heritage from whence such narratives came. In other words, it is important for us to consider, for instance, the manner in which postmodern structures have affected the ways that video game narratives are structured. And video games like Pony Island, The Magic Circle, and Until Dawn, it would seem, tell the types of stories that, although different in structure and form than other more “traditional” types of texts, have the potential to utilize, for one, a postmodern focus to alert us to the systems of meaning in which we are located. Thus, video games, too, of course, have the potential to make meaning.

Such potential seem especially relevant when thinking about where our narrative forms are headed—what now for the manner in which we think about postmodernism and narrativity? And what now for the manner in which we think about video games? Indeed, if the evolution of video game narratives is any indicator, the manner in which we tell stories will continue to change, and it is vital that we, as scholars, become willing to change along with it. Because, to be sure, things like the metanarrative moves being made in the realm of video games seems to highlight the fact that it is a realm full of potential and one ripe for exploring.

One thought on “Gaming as Complicitous Critique: Postmodernism, Metafiction, and Video Games”

This is interesting, though I’d like to see a more specific consideration of what games like The Magic Circle and Pony Island are complicit with even as they perform their critique: is it only traditional narrative structures, or is it some of the specific problems and prejudices those structures have helped sustain?

That, to me, is the most important aspect of Hutcheon’s theory: that you don’t have to achieve a (mythological) kind of purity to perform cultural critique, but also that we should pay attention to where and how critical works are problematic and even support the very things they’re calling into question.