In a recent article, “Apparent Feminism as a Methodology for Technical Communication and Rhetoric,” Erin Frost proposes a new methodology through which to understand the impact of technology and technological documentation: apparent feminism. Apparent feminism, she writes, “seeks to recognize and make apparent the urgent and sometimes hidden exigencies for feminist critique of contemporary politics and technical rhetorics” (5). Why “apparent”? Because technical communicators work in the public realm, where the need for feminist intervention is apparent (she avoids the word visible because 1) it is ableist language and 2) apparent has methodologically more depth). Methodologically, apparent feminism rests on a myriad of authors from many disciplines, and it works to push an intersectional, social justice-centered motive for technical communicators. Put simply, she makes social justice, ethics, and bodies the most important part of the work of technical communicators.

As I’m reading through this article I can’t help but make connections to game studies, perhaps because this article was published very close to a special issue on gaming in technical communication. In Game Studies (proper), culture has been a primary concern. This, I think, has come out of both urgency (people are constantly attacked, harassed, and threatened on a daily basis) and necessity, since representing bodies digitally forces a certain set of questions to be asked, as opposed to the seeming disembodiment of technical documents.

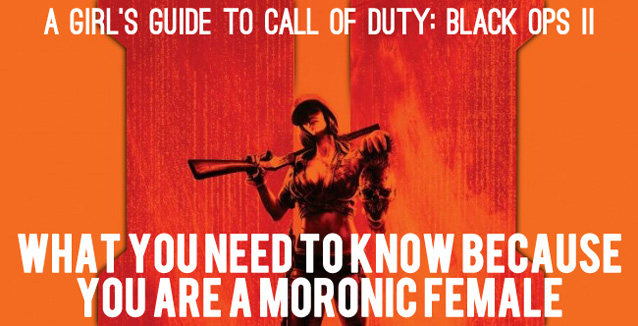

But here is the rub, and why I’m writing this post, technical communication needs something gaming has (an obvious tie to cultural and intersectional perspectives), and gaming needs something technical communication has (obvious repercussions for real bodies). Because each field is lacking, it makes it easy for other practitioners to ignore the consequences of their technology. So what would an apparent feminism methodology bring to gaming?

Apparent feminism has three main aims: make apparent the need for feminist interventions, hailing nonfeminists as allies, and demystifying the relationship between feminism and efficiency. I think we at NYMG and others, such as ADA: Journal of Gender, New Media, and Technology and Critical Gaming Lab, have the first part covered. We publish articles daily showing the need for feminist interventions in gaming (though I would add and stress the necessity of intersectional feminism in games. White feminism is actually extremely detrimental to women and people of color and LGBTQ+ folks and pretty much everyone).

Now, number 2, hailing nonfeminists as allies. This is a difficult one for me personally. I think many scholars in game studies who do not at least marginally work toward ethical and cultural goals is missing a cornerstone of what it means to do Game Studies proper. You can’t “do” games without recognizing the history of problematic depictions of women and cultures and engaging with the toxic community. Frost defines this tactic as building coalitions with those who might appear to be feminist in their activism or ideological perspectives but do not embrace the label” (14). It’s an interesting question: what do we gain by exposing work that fits feminist aims as feminist, even if the author does not recognize it as such? I struggle with this question, because I often claim that work such as feminist rhetorical methodology is simply sound methodology. I personally do not feel defensive of the label “feminist.” But I have no doubt there are many implications of forcing the label on another’s work, particularly because of the damage White feminism has done. This may be more complicated than it appears. However, if we take the core idea to be coalition building and ally building, then I am on board. I worry sometimes, though, that I spend so much time dealing with what is currently on fire that I miss opportunities to make friends with people who could be holding a bucket of water.

Efficiency is probably one of the most contested terms in technical communication. A lot of unethical work has been done under the guise of efficiency. It can and does kill people. I think the same could be said of certain terms in gaming; fun, for example, is a defense people use to convince themselves that something racist they laughed at—for example—isn’t important. It’s just a joke. It’s just for fun. Technical communication and games may fall on opposite ends of the spectrum, but face the exact same problem: people use the goal of the medium to ignore, or worse as an excuse, for unethical behavior.

I don’t know what the three main goals for apparent feminism would be in the gaming world. I think that the methodology has some very interesting ideas, though, and practical ways that we can further intersectional feminist goals without alienating people. Further, I would hope that more crossover between technical communication and game studies would lend toward gaming being seen as having more concrete consequences and open up ore spaces to address the cultural consequences of technical communication.

The article referenced, “Apparent Feminism as a Methodology for Technical Communication and Rhetoric,” is published in the Journal of Business and Technical Communication Vol. 30(1)