Many games, particularly smaller indie games, present limited experience, and these limitations can manifest in myriad ways. Firewatch takes place over a single summer. Depression Quest is all text, with text options denied as its driving mechanic. Reigns is a series of yes/no decisions. Some games, though, ask you to accept other limitations, limitations embodied in a certain way. Games like Hacknet place you at the console; The Beginner’s Guide walks you through a confession. A Normal Lost Phone is limited in this way — all play takes place inside the titular phone, but there’s a twist. Seems straightforward. But the nature of the story turns this simple limitation on its ear.

Spoilers for A Normal Lost Phone follow.

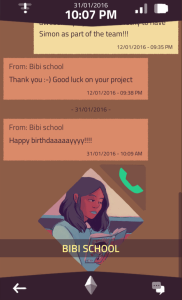

Not only are you, the player, the finder of the phone, handed a window into someone else’s life, that someone exists in a marginalized space. As you unlock more and more hidden areas, you learn more about the owner’s life and story, but because so much of the content is locked, you’re put into that role. Games like 12 Hours ask the player to empathize with someone in a position of intersecting marginalized identities, and to embody that role, but A Normal Lost Phone takes it further: here, you are not simply asked to think like the phone’s owner. You have to, in order to advance. You can’t try out different options. Essentially, the narrative is linear, or more properly, it’s over. By the time the player enters the game, all that’s left to do is witness. But much of the game’s content is password-protected. Figuring out the first of these passwords is easy, but subsequent obstacles are a little more difficult, and require careful examination, and in some ways, thinking like the phone’s owner.

It’s a powerful way to design an empathy game. Without thinking, the player begins to relate to the phone’s owner, even if that experience is so far outside of their own as to be difficult to understand. Slowly, the player moves from voyeuristic to sympathetic, and it happens naturally, as the game progresses. The only way to avoid it completely is to refuse to play. I mention 12 Hours above because it takes a similar tactic, but it’s still structure more like a standard game, offering the player overt choices. When faced with choices, even if we’re trying to build a character, we often want to “win.” There’s no winning here. There’s only witnessing, and in witnessing, we become.

It’s a powerful way to design an empathy game. Without thinking, the player begins to relate to the phone’s owner, even if that experience is so far outside of their own as to be difficult to understand. Slowly, the player moves from voyeuristic to sympathetic, and it happens naturally, as the game progresses. The only way to avoid it completely is to refuse to play. I mention 12 Hours above because it takes a similar tactic, but it’s still structure more like a standard game, offering the player overt choices. When faced with choices, even if we’re trying to build a character, we often want to “win.” There’s no winning here. There’s only witnessing, and in witnessing, we become.

Ambient adventures like this, that are fully linear, often don’t grab me as much as games that offer branching narratives, but as I revisit A Normal Lost Phone, I find more and more that the approach is more clever than it first appears. On its face, the game has a message, but it’s the more subtle becoming underneath the message that makes this a worthwhile experience.

Not everyone has the same read on this as me; at Kotaku, Heather Alexandra took the game to task (even more spoilers there) for making a choice the phone’s owner, Sam, might not have made, a choice that could be seen as a violation of privacy, and certainly a violation of consent. It puts the player in a potentially uncomfortable position; again, you can’t advance without this moment. But by that point in the narrative, the player has already begun to think like Sam. The player has spent the game becoming, and the becoming is what’s at stake here. Not a win. Not even discovery. Just that simple act of becoming, something beyond empathy, beyond connection.

I won’t pretend the game is for everyone. But it’s an experience that’s kept me thinking.