Last year I walked into a store dedicated to board and card games for the first time. I love board games but it is not always easy finding a store that is the analog equivalent to GameStop. And usually when I do find them, they are far away. So when I walked in I was super excited – there were so many games I hadn’t seen, but one in particular caught my eye – Mysterium. I thought the artwork on the box was beautiful and when I asked the manager what the game was about I was even more excited. I got the game over the holiday break and have played it a few times since then.

The game is a cooperative experience in which one player is a ghost who cannot talk or make noise. They can only knock on the table at specific stages, once for ‘no’ and two for ‘yes’. The rest of the players, however many, play as psychics trying to discover how the ghost was murdered via vision cards. It is like a coop Clue in which you need to find the person, place, and weapon. One of the reasons I really like the game is due to the use of silence as a game mechanic. It is not an implementation you see very often. When I started to think about it a bit more I realized how unique the idea of silence as a mechanic is, how impactful it can be, and how video games and analog games use silence as a mechanic differently.

When I say using silence as a game mechanism I mean that it is used in a way that is integral to play. For video games, this means using silence beyond just cutting out the music or using it as a way to add to the narrative and atmosphere. For analog games this means silence is not just a product of good practice or boredom. For both, it is something the player must consciously be aware of in order to progress with the experience. So when P.T uses silence to enhance jump scares and suspense or when Undertale remains silent in parts to convey a sense of calm this is not a game mechanism but an implementation of silence within the musical score or physical game world. When Poker and Chess players remain stoic and calm this is considered good practice. Or when two 24 year olds are playing Candy Land before a grad meeting and being perfectly silent I am guessing this has nothing to do with the strategic nature of the game and hiding one’s moves. Neither is actually a game mechanic.

Mysterium uses silence as a rule and an implementation of play that the players must work with. While it is a construct that can add realism to the play and narrative (ghosts can’t talk) it is also required in order to play the game and the ‘ghost’ must maneuver around this hindrance. They must not give anything away with gestures, facial expressions, or other noises. If the ghost was allowed to talk it would ruin the point of the game and destroy the one source of conflict in the game. One could argue that silence in the game is the real antagonist as it is the sole source of challenge to be overcome and played with in the game – not that actual murderer. Therefore, silence in Mysterium moves beyond aesthetic and decorum. Rather it is an idea that is explained in the rules and is composed mechanically through a need for conflict.

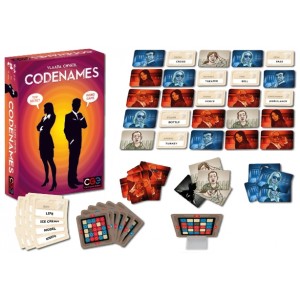

Another analog game that uses silence in similar way to Mysterium is a card game called Codenames. In this game cards with (usually) one word are laid out on the table. Players assume the roles of spies trying to crack the code. One player from each team is allowed to give them a one word clue each round and then they must remain silent the rest of the game. The goal is to get the other players on your team to guess as many cards per one word clue given. Again this is explained in the game rules and the “sneaky” spy must not indicate anything beyond the one word given – no noises or facial expressions. While this is not the only source of conflict, as the teams are playing against each other and racing to get all their cards first, it is certainly a major one. Without this silence the point of the game would again be ruined.

game that uses silence in similar way to Mysterium is a card game called Codenames. In this game cards with (usually) one word are laid out on the table. Players assume the roles of spies trying to crack the code. One player from each team is allowed to give them a one word clue each round and then they must remain silent the rest of the game. The goal is to get the other players on your team to guess as many cards per one word clue given. Again this is explained in the game rules and the “sneaky” spy must not indicate anything beyond the one word given – no noises or facial expressions. While this is not the only source of conflict, as the teams are playing against each other and racing to get all their cards first, it is certainly a major one. Without this silence the point of the game would again be ruined.

It is much more uncommon for video games to use silence as a game mechanic. Part of this is due to the hardware and technology and the other is due to the nature of the medium and how it has evolved. Video games are a visual and auditory system. They have soundtracks, voice recordings, and sound effects (a few analog games have narrators and soundtracks – One Night Werewolf – but this is extremely uncommon and is a relatively new development).

Alien: Isolation is a great example of silence as a game mechanic. In this game you are playing Amanda Ripley as she tries to evade an alien, robots, and other brutal humans amid a dying space station. There is a mode in this game where you can activate sound detection through your mic. The game then listens to the real world around you and if your roommate walks through the front doo r or your cat meows – sorry ‘bout cha – but the alien just heard you and now your dead. It adds an incredible tension and realism to the game but it is also something the player must actively be aware of as they are now playing with this idea of silence. When the player activates this setting they are told how the game will respond to this – the rules of the game system and the programming that said system adheres too. While it is a rule for the system it is not a rule for the player. Here the player doesn’t have to be silent but it is silence that will get you through the levels. Any amount of sound will add to the difficulty, especially depending on the location and how many enemies there are.

r or your cat meows – sorry ‘bout cha – but the alien just heard you and now your dead. It adds an incredible tension and realism to the game but it is also something the player must actively be aware of as they are now playing with this idea of silence. When the player activates this setting they are told how the game will respond to this – the rules of the game system and the programming that said system adheres too. While it is a rule for the system it is not a rule for the player. Here the player doesn’t have to be silent but it is silence that will get you through the levels. Any amount of sound will add to the difficulty, especially depending on the location and how many enemies there are.

The game I wrote about last week, Orwell: Keeping an Eye on You, also uses the idea of silence as a mechanic in an interesting manner. The idea of ‘silence’ in this game is a bit more abstract and revolves around philosophical ideas and notions of withholding information. In the game you are tasked with reporting information of (mostly) your choice. You can choose to remain silent on certain topics or give personal data on subjects you are investigating to the secret government organization known as Orwell. Your choices will have severe consequences. At many times it can be hard to choose whether or not to disclose information. Near the end of the game you can either report information on corrupt government officials or violent subjects that have become aware of Orwell’s existence. Both sides have done awful things and this provides moral and ethical conflicts for the player.

In both of the video games silence is used as a means to add tension and conflict, much like analog games. However, silence in video games is more open ended in the ways that it can be played with. In the analog games aforementioned silence is required by the game and for the player but in the video games it is not. It is much more exploratory in nature. While both add difficulty to the game, it is video games that interrogate this difficulty. As a result the level of difficulty can change from time to time.

This is not to say video games are more successful, but it is interesting to see the different ways the two types of games handle such a unique method. Silence is a really cool mechanic that I think should be explored more. It can add to both narrative and play in more ways than just gaps in a musical score. However it should be handled with some caution and care. If designers are going to include a way to play with silence they should be aware of what or who is being silenced, what this says about the story, and what this says about real life. Mysterium, Codenames, and Alien: Isolation are able to avoid harmful implementations of silencing a person/player through randomized gameplay or using silence in a realistic way that isn’t tied to representation. While I believe Orwell also does a good job of using silence it definitely explores and exacerbates ethical dilemmas involved with silence. Regardless, as with any mechanic, it is an idea that should be thoroughly thought through – and when it is, is something that can be really fun to play with.

5 thoughts on “Not Another Word: Silence as a Game Mechanic”

Great idea for a critical focus–and I appreciate the survey you provide. It got me thinking about the broader issue of limiting talk.

The Quiet Year came to mind. It doesn’t use silence per se, but does impose strict rules on how players speak to each other. This governs the formal process of group discussion (during which players can say 1-3 sentences, then must be quiet and let the next player contribute). And it governs the informal moments; for example, when other players’ add a drawing to the group’s collective map and the emerging narrative it describes. Ultimately, the rule limits “lawyering,” affirms the theme of collective cooperating and creativity, and helps keep the game in “yes and” mode.

Thank you! I haven’t played the Quiet Year but it sounds really interesting. I’ll have to give it a try. It also sounds like a passively tense game if that makes sense. I can imagine playing with my friends and it being hard for each of us not to speak up if the narrative took an unwanted shift! But at the same time we all love telling stories – I guess we’ll just have to try and see, sounds both creative, unique, and fun.

The “Boards” have it. Good to see the games, including boards” being evaluated. Thanks.

One major problem with silence in Codename is that it removes players from the game. Not only is the player allowed to say only one word, so his thinking is undisclosed, but also the other players are expected not to talk to much, so as not to communicate with the boss. Personally I find it problematic for a party game, where interaction seems crucial.

That’s a good point. I definitely think that each game implements silence with varying degrees of success. However, I think it also depends a bit on preferred played style by the players and the situation. I know people that find Codenames really boring. The people I play with really like it. We usually either play it while doing homework (the person saying one word thinks about what to say while the others do homework then when the one word is given the roles switch). But most of the time we play at board game nights and there is still a lot of interaction and talking going on. Its slightly against the rules but the two “word-givers” often talk to each other while hiding their faces since they can see each others cards and making sure the other two players can’t hear. The other two players are usually talking to each other, sometimes playing hand held devices sometimes still trying to figure out a previous word while discussing their thoughts with each other. I like the game but I can clearly see why people would find it boring/problematic etc…