Late last year, I stumbled across an ad for Mosaic, a film-based interactive story app helmed by film director Steven Soderbergh and starring Sharon Stone. Intrigued, I downloaded it immediately, but I never got very far. At the beginning, at least, “interactivity” seemed nonexistent, and while I appreciated the story for featuring a sexual, strong female lead over the age of 30, the structure felt more like an episodic television presentation than anything gamelike. I considered finishing but finally deleted the app.

Fast forward to last month when I caught a similar ad on HBO presenting Mosaic as a show. Aha, I thought; this will be a much better presentation. I won’t be trying to pay attention to my phone and thinking about shoehorned ludic elements. But what was more interesting to me is that though Mosaic definitely felt like a game—well made or not—it wasn’t being called a game. In fact, Soderbergh specifically worked to avoid making Mosaic complicated in the way of games, but in doing so, has perhaps asked us to confront again the definition of “game” and the boundaries of the concept, and while I couldn’t get into the story of Mosaic, I’m definitely up for interrogating, again, where we draw lines around games.

Here is the description from the app store (trimmed for relevance):

MOSAIC is a new film experience from Academy Award®-winning director Steven Soderbergh, starring Sharon Stone, Garrett Hedlund, Jennifer Ferrin, Paul Reubens, Devin Ratray, Frederick Weller, and Beau Bridges.

In MOSAIC, as in life, the path you pick affects your perception of reality. What one viewer may consider a fundamental fact on one path may be an insignificant piece of trivia on another — or may not even be a ‘fact’ at all. As its title suggests, MOSAIC isn’t complete until all the pieces are viewed in their proper perspective.

MOSAIC lets you experience the story from multiple perspectives, going deeper to see the big picture:

– Film view: Watch the film in full-screen, immersive mode.

– Choice moments: Select which character’s perspective you want to adopt to continue your journey.

– Discoveries: Go behind the scenes to check out voicemails and emails between the characters, police reports, news clippings and more.

– Look again: Go back and view the perspectives you missed to get the full picture.

Here, Mosaic is called “a film experience,” and on Wired, a headline claimed the app and platform would change how we watch television. How? By changing the overall shape of film and television, and how we experience it. Games are experiential; we enter a space, accept and adopt its rules (unless we set out to exploit them, as with mods and glitches), and experience a given or chosen perspective. Mosaic asks the viewer to enter the story through a chosen perspective while accepting and adopting its rules-rules that mean you can’t change the narrative, but you can experience and study it in a way that appeals to you.

Mosaic, then, is a game that isn’t a game, but perhaps only because its creator chose to discard the ludic label. But if Gone Home is a game, if The Beginner’s Guide is a game, if Submerged is a game, then Mosaic should be as well. And yes, I’m aware there is a contingent of people who argue against these experiences as ludic experiences, but the boundaries around what we consider a game are flexible; they shimmer and change as we create new experiential storytelling forms using rules-based systems.

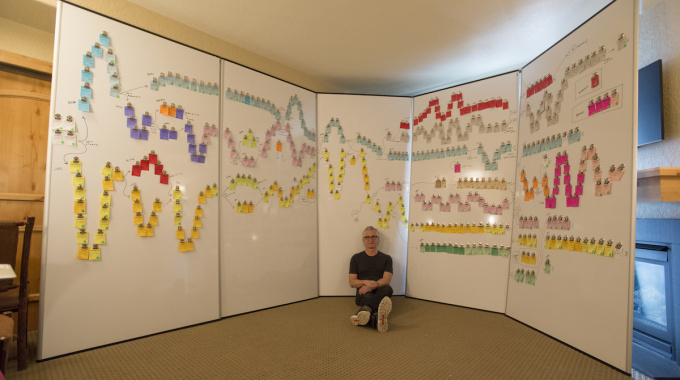

Which reveals what may be the central question: Is Mosaic a system? Here’s writer Ed Solomon in front of the storyboard:

It’s difficult to see the connections and flows in this image, but they are there, same as individual pieces in a Twine game, or similar renderings in other platforms. And of course, if we dig down, the platform for creation is a system, the app is a system – but that’s not really what’s at stake. Is the story a system? Is any story not a system of sorts?

Is the creator’s will what decides, or can I, on my own, decide Mosaic is a game?

I don’t have answers for these questions, but they intrigue me as much as the people who play countless phone and tablet games but never call themselves gamers. Both situations leave me wondering if it’s the label that’s the real issue, the reason for outright rejection on Soderbergh’s behalf. If he called this experience a game, would he miss his target audience? And does the label even matter at all?

You can reach Alisha at her website.