As October draws ever nearer, an influx of horror games has begun to hit the market in an attempt to fill the creepiness quota so in demand during the Halloween season. Though the settings and contexts differ from game to game, the asylum, particularly the abandoned and decrepit asylum complete with minimal lighting, is a popular and frequently used setting for these thrillers. And, more often than not, the villains or enemies are the “crazy” or “insane” inhabitants of the asylum, out to do the player harm out of rage and an uncontrollable violence. Despite the essential repetition of this concept, it is, for the most part, often an effective one in generating fear in the player: we get immersed in the fear and trepidation of the player character and dread what could potentially be lurking around the corner. We internalize the constant paranoia involved with traversing a setting in which nearly everything is out to get us. But do we ever stop to examine just why these characters are routinely made to be the villains and what effect it has on real life representations of people with mental illness? With this in mind, this week I would like to discuss the way that mental illness is presented within video games, some examples of it, and the harmful effects it can have on public and personal opinions off those who have mental illness.

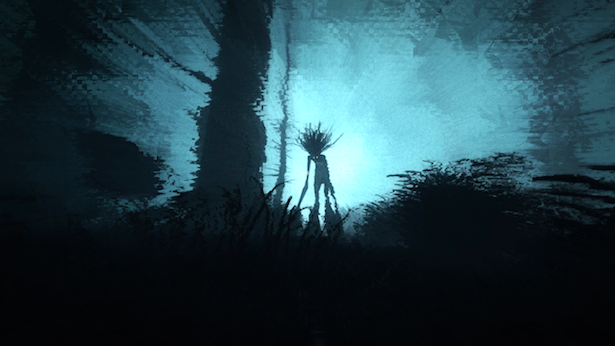

Many representations of mental illness in video games both in the game itself and in advertisements stigmatize it, marking it as something which makes a person dangerous, violent, or not normal. Because of this, a variety of tropes often arise when a character with mental illness is created. As I was searching for a game to write a review on for this month, I came across the latest example of this in the form of the indie game Outlast, which was released on Steam this week. The concept seems fairly simple: you play a journalist named Miles Upshur who becomes entrapped in Mount Massive Asylum, a previously abandoned asylum transformed by a suspicious corporation into a hub of research. Within the asylum, former patients, now crazed mutants, are out to get you and it’s up to your own wits to survive. The primary source of fear, as advertised by the game itself, comes from the fact that these enemies are “crazy.” While it may be effective as a game mechanism, it nevertheless brings forward a number of harmful associations in which the mention of mental illness and being “crazy” is reason to not only make these characters the villains, but to justify the extent of often unexplained violent motivations. Oddly enough, the game, in narrative or design (such as cells in which the “patients” lived being clearly inhuman), often depicts the asylum itself and the treatment given to those trapped in there as distinctively abuse and negative. Though conceding a historical sympathy or sensitivity of sorts to the real conditions people with mental illness faced in asylums until as late as the 1970s and 80s, they still simultaneously deny any sensitivity or degree of relatable capacity to the, more often than not, psychotic enemies or underlings.

The noticeable lack of realistic, appropriate, and approved characters with mental illness as well as the frequency in which the crazed enemy trope is used points to the severity and widespread control this malicious representation has in gaming. The list of offenders is rather long, but I will illustrate a few here. In Batman: Arkham Asylum, the hero Batman not only faces a variety of markedly deranged main villains and bosses but also hordes of nameless residents of the asylum. Perhaps one of the worst offenders includes Manhunt 2, which, with a similar storyline to Outlast, involves the player character having to battle through the asylum filled with people trying to kill him, which so reinforced the murderous and violent stereotype of people with mental illness that the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) criticized the game and called for it to be heavily edited or recalled. Even the Sims 3 offers the player to chose the “Insane” trait for their Sim, which causes the Sim to be likely to be rude to other Sims, act like animals, investigate neighbors’ trash cans, and dress oddly, contributing to a, although nonviolent, stigma that people with mental illness are “weird.”

The depiction of people with mental illness as likely to commit acts of violence or more likely to be murderers, thieves, and perpetrators of other violent offenses is not only incorrect (they are actually more likely to be victims of it than the one committing the act) but also largely responsible for the hesitancy and negativity in which mainstream society interacts and views them. This is not a theoretical discussion either, as this affects real people who, in addition to facing any challenges associated with mental illness, must also assure people that they are not the “crazy” persona so often depicted in popular culture. Even when the offense is not intentional or is exaggerated to make it unrealistic, subtle biases may still be conveyed to the player.

Though this issue has begun to be properly addressed in other mediums, I believe such exposure is rather lacking within gaming rhetoric and critique and should be important to note when designing characters, especially those filling the role of the villain. Although certainly not the first or only medium to exploit mental illness, games with these themes, particularly horror games, cast a harmful stigma on real people with mental illness that directly affects their quality of life.

2 thoughts on “They’re Mad, I Tell You: Portrayal of Mental Illness in Video Games”

If anything the inmates in Outlast reminded me of the Splicers in Bioshock – Normal people driven to acts of violence by isolation and tortuous conditions. You have to ask yourself what anyone would do in that situation, “insane” or not.

As far as I’m concerned the inmate in the cafeteria more than makes up for any stereotypes people would pull. He provides a human face to the situation, and this act creates one of the most memorable and haunting moments in the game.

Very good article. The term ‘mental illness’ covers so many different types of disorders & conditions and I think society just likes to lump them all together, and anyone who is not “normal” mentally struggles to find acceptance and help because of that. Someone with anxiety or depression or OCD has a mental illness but they are likely to be completely different from a raging violent psychopath. Yet both struggle in society. Obviously, someone who is violent is a different kettle of fish but the underlying problem is of a society unwilling to tackle the issues of mental illness as a whole (and of governments who don’t put enough money into programs and structures).